LABOUR FORCE SURVEY

Unemployment for black South Africans is worse today than before 1994

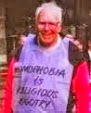

Photo: Flicker

On Thursday, Stats SA released its latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey. The record numbers of unemployed should send a shock through our system and compel an immediate reconsideration of our economic policy. The toll on poor people is now unbearable.

South Africa is literally not working. The numbers out on Thursday suggest that a recovery is barely being staged. At 14.7 million, the number of people employed in the country remains far below even the disastrously low level of 16.4 million just before Covid-19 hit South Africa. To put this in perspective, there are 39.2 million people aged 15 to 64 in the country (the “working age”). Between July and September of this year, only 37.5% of them were in work. This is barely more than half the world average.

South Africans, particularly black working-age South Africans, are less employed today than in 1994.

The narrow or strict unemployment figure sits at 30.8%, the highest on record, exceeding even the first quarter of 2020 figure of 30.1%. However, this alarming rate does not capture the full picture. There are still 10% (1.7 million) fewer jobs in the country than in January to March of this year.

To be classed as strictly unemployed, you must have actively looked for work over the past month. The number of people who have completely given up looking for work has increased by 2.7 million since before lockdown.

Only 543,000 jobs have returned to the market of the 2.2 million lost since April. Informal workers such as traders, own-account workers, domestic workers and those in micro-enterprises, who engage in the most survivalist and entrepreneurial activity in the country, accounted for 292,000 of the returning jobs. However, as the most financially vulnerable group, there are sadly still 16% fewer people employed in this way than in the first three months of 2020.

How unemployment impacts on the poor

Ntsikelelo Msweswe, a 36-year-old volunteer at the Gugulethu branch of Organising for Work (OfW), the unemployed movement I am associated with, says that the “lockdown came and made things worse for me as I have to sit at home and wait for NPOs [non-profit organisations] to help us to have food”. Despite feeling “very helpless”, Msweswe says that, “I would love to do something for people with criminal records … to share the skills and the energy I have towards working.”

OfW, which launched in 2018, does grassroots community organising to alleviate unemployment. It has branches in some of the highest unemployment areas of Cape Town. Its model is to organise unemployed people to run their own branches that support people in their search for work.

The branches – run for free by unemployed volunteers in public libraries – also push for better treatment of jobseekers and act as communal spaces that make searching for work a little less solitary. They are in a sense free job centres connecting unemployed of all ages, education levels, abilities and criminal records directly to employers from where they live.

Msweswe, as well as many other volunteers and members of OfW, has been involved in local organising efforts like Cape Town Together that arose in response to the pandemic. More than ever, government failure in South Africa has placed the burden of alleviating poverty and worklessness on individuals.

Thomas Piketty, a French economist regarded as the world’s foremost expert on inequality, describes South Africa as an extreme case of an “inequality regime”. In his latest book, Capital and Ideology, he lays out in detail how inequality regimes around the world result from choices made by the political classes – choices that are never as forced by circumstance as they are later portrayed.

Disgracefully, inequality in South Africa, along with unemployment, has worsened since the end of apartheid. Piketty, as well as many local economists, will tell you that the choices made since 1994 were made instead of many other competing and feasible options. For example, the choice by the ANC in the first two years of democracy to scrap rather than carry out the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) – the cornerstone pledge of their 1994 national election campaign – haunts us today.

Fast-forward 26 years and President Cyril Ramaphosa speaks of an Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan that promises some of the housing, infrastructure and manufacturing of the RDP. The past two and a half years of his speeches have contained a relentless recycling of economic plans that are never realised, dead or inadequate.

They make it hard not to see him as anything more than a Baghdad Bob, a farcical character promising victory in the face of catastrophic destruction.

The unemployed members of OfW are best placed to know how empty his words are.

Millicent Kamase, a 39-year-old member of OfW’s Site B Khayelitsha branch, summarises them well when she says that his promise of 800,000 public jobs “will never happen. We’ve been voting for years and are still unemployed.”

Ramaphosa’s recovery plan and R500-billion stimulus were revealed last month in the National Treasury’s Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement to be, in reality, a reduction in spending over the next three years through regressive austerity. For an excellent summary of the “puffery and confusion” of Ramaphosa’s plans and Treasury’s defunding of them, read Duma Gqubule’s detailed and investigative analysis.

What appears not to occur to the president nor to his finance minister, Tito Mboweni, is that there are other options.

For example, a new-money stimulus and an infrastructure-led jobs programme which actually creates jobs and builds infrastructure that supports and reaches the poor. Their choice to go for austerity in the midst of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression is the worst of all possible options.

Comparable economies such as Brazil and poorer ones, such as India, which have higher public debt than South Africa, have massively increased their spending and debt to cover the cost of the pandemic.

Not only is the national government’s approach stalling the South African economy, tax collection and job creation, but the cost of the pandemic is also being placed disproportionately on the country’s poor in the form of worklessness, a reduction in public investment and contraction of basic services in health and education.

City of Cape Town hoards while people starve

Of course, it is not only failures at the national level that hold back job creation and make job seeking even more gruelling, discouraging and unaffordable than it needs to be. The City of Cape Town approved its budget in June this year, during the darkest days of lockdown, retaining R4.6-billion as surplus in 2020/21, R6.2-billion in 2022/23 and R5.4-billion in 2023/24.

It is an extreme indictment of the hypercapitalist, socially aloof city council and its executive not to direct these funds towards, for example, public employment, township infrastructure and free public Wi-Fi.

As I write, the city’s public libraries, virtually the only sites of free public Wi-Fi in poorer areas and the sites of OfW branches, are still operating unnecessarily restrictive lockdown policies.

Life was hard before Covid-19 for unemployed South Africans. The paltry R350 per month that will continue to reach a minority of those not working until January next year, pales in comparison to lost income related to the pandemic.

As Mnyamezeli Sibunzi, a 26-year-old member of OfW’s Langa branch, puts it: “Finding work now is something that I wish, I even dream about… I’ve never been so broke in my life.” DM/MC

Ayal Belling is a founder of the unemployed movement Organising for Work. He previously worked in finance and technology in London and Cape Town. He can be contacted at ayal@ofw.org.za.