SIDLEY (nee DE SAXE)

Jeannette Molly (always called Molly) De Saxe died in Johannesburg on

Saturday 27 January 2018, aged 93. Molly was born in Johannesburg on 18

March 1924 where she lived all her life. For the last 10 years of her

life she had suffered from dementia and was in a nursing home.

She will be remembered with love and affection by her brother Jos

(Mannie) De Saxe, his family and his partner Kendall Lovett in Melbourne.

Our deepest sympathies to her daughter Patty and granddaughter Kate in

Johannesburg.

Molly had many friends and relations in South Africa and elsewhere who

will remember her for the bright and bubbling personality she had been for so

much of her life.

Sadly missed by her brother Jos.

Molly had one only ever visit to Sydney in June 1994 for two weeks and it was all too short. I took her all over and we saw what we could in that short time.

We had a little dinner party on the night she arrived - my partner Kendall Lovett, his sister Julie Daley, Molly and me. Two sets of brother and sister.

Gary Jaynes gave us the roses for Molly - "ROSES FOR REMEMBRANCE"? It was very kind and thoughtful of him and very much appreciated.

Just Molly and me...................................

................................with our grandmother - our mother's mother Pesa Kuper.....

---------------------------then Barry made three!!

HUMAN RIGHTS & EQUALITY FOR ALL,FREEDOM & JUSTICE FOR PALESTINE, ZIMBABWE, BURMA, EVERY COUNTRY SUFFERING FROM WARS, DROUGHTS, STARVATION, MILITARY ADVENTURES, DICTATORSHIPS, POLICE STATES, RELIGIOUS OPPRESSION, HOMOPHOBIA, CENSORSHIP & OTHER OBSCENITIES.INTERNATIONAL ASYLUM SEEKER SUPPORT

A BLOG SITE, "BLOGNOW" COLLAPSED IN 2009, SO USE THE GOOGLE SITE SEARCH ENGINE

29 January 2018

RACISM NOW THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT'S WAY TO WIN THE NEXT ELECTION

Plus ca change - the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Racism was introduced to Australia on 26 January 1788 and it has been a vote-winner ever since.

It was, after all, the British who were at the forefront of the ntroduction to the world of concentration camps in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902.

After the genocide got into full swing during the 19th century, the race card was an easy one to use in every field of endeavour as people needed employment and other services from governments and as is so typical of governments who have set up institutions with race barriers it is generally the underclasses who suffer most.

So, who are the underclasses?

Well, first it was the indigenous population, then it was the Chinese miners, then the Japanese pearl divers, and so we go through every wave of immigrants and asylum seekers and refugees, until we get to - wait for it - the Africans who are mostly black.

Not only are they black, as the media and politicians tell it, they form gangs and do terrible things. Notice how selective they all are when it comes to other groups who do the same or even worse, and so, who gets the blame for everything, despite evidence to the contrary?

Well, who has low ratings and needs to win the next elections?

Racism was introduced to Australia on 26 January 1788 and it has been a vote-winner ever since.

It was, after all, the British who were at the forefront of the ntroduction to the world of concentration camps in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902.

After the genocide got into full swing during the 19th century, the race card was an easy one to use in every field of endeavour as people needed employment and other services from governments and as is so typical of governments who have set up institutions with race barriers it is generally the underclasses who suffer most.

So, who are the underclasses?

Well, first it was the indigenous population, then it was the Chinese miners, then the Japanese pearl divers, and so we go through every wave of immigrants and asylum seekers and refugees, until we get to - wait for it - the Africans who are mostly black.

Not only are they black, as the media and politicians tell it, they form gangs and do terrible things. Notice how selective they all are when it comes to other groups who do the same or even worse, and so, who gets the blame for everything, despite evidence to the contrary?

Well, who has low ratings and needs to win the next elections?

Labels:

Australian politicians,

concentration camps,

racism

28 January 2018

PRIME MINISTERIAL HYPOCRISY SPILLS OUT YET AGAIN!

How much longer are Australians going to be prepared to put up with the hypocrisy of the politicians whose rantings and ravings get worse and worse every day?

Today, Sunday 28 January 2018, we have the current prime minister raving on about the Holocaust, while his government locks the indigenous people in prisons and areas around the country which are worse than prisons and concentration camps , does the same with asylum seekers who are treated worse than animals - they treat their pets better than the human beings in Papua New Guinea and Nauru - and pontificates abut human rights and what needs to be done in Australia and around the world.

One really needs to carry one's vomit bucket around with one where ever one goes, and to be careful to spill it only on politicians.

Today, Sunday 28 January 2018, we have the current prime minister raving on about the Holocaust, while his government locks the indigenous people in prisons and areas around the country which are worse than prisons and concentration camps , does the same with asylum seekers who are treated worse than animals - they treat their pets better than the human beings in Papua New Guinea and Nauru - and pontificates abut human rights and what needs to be done in Australia and around the world.

One really needs to carry one's vomit bucket around with one where ever one goes, and to be careful to spill it only on politicians.

HUGH MASEKELA: NO ROOM FOR COMPROMISE

January 26, 2018

It was less than a year ago on March 15, 2017 when I sat down with Hugh in Sandton to talk about his support and participation in the second Kwame Nkrumah Cultural and Intellectual Festival. I had contacted Hugh through our mutual cultural worker friends to request that he participate in the Festival that was scheduled for June 25, 2017. In the communication, Hugh had expressed an interest in coming to the public lecture that I was scheduled to deliver on March 14 at the University of Johannesburg. Before the lecture he had sent his regrets that he could not come to the lecture but dispatched Rapelang Leeuw to collect me so that he could discuss his contribution to this festival.

The theme of the Festival was Education for Transformation.

From the outset of the discussion, Hugh Masekela made it clear that he supported the idea of the Festival, and that he would travel to Legon, Ghana and perform at his own expense. After explaining the nature of the enterprise to promote the ideas of Kwame Nkrumah for a free, emancipated and socialist Africa, Hugh called up Mbongeni Ngema (composer and director of Sarafina fame) to discuss how the Sarafina expression of defiance could enhance the festival. After brainstorming for two hours of how much it would cost to bring the group of over 70 performers to Ghana, we agreed that we would look for sponsors and to see the availability of the Ghana National Theatre for their performance in Accra.

Hugh was excited about his planned trip to the USA in May 2017 to promote his new album of 2016, No Borders. I left Johannesburg with the optimism that Masekela had fired up in his enthusiastic support for this new push for African Unity and for politically educating the youths about the tasks ahead. In May when I contacted the manager to discuss the logistics of his participation in the Festival, we were informed that Hugh would not be well enough to perform. We did not then know that Hugh would never perform again. Hugh fought a long battle with prostrate cancer and joined the ancestors on January 23, 2018.

For over 60 years Hugh had been at the forefront of world revolutionary trends and made his mark at the site of the global anti racist struggles. It was fifty years ago in the midst of the ‘68 uprisings when Masekela used his trumpet to inspire the youths who were then fighting for revolutionary change all over the world. His album and the lead song, Grazing in the Grass, was a song of inspiration. His sounds of struggle, inspiration, revolutionary change and love are now part of the history of revolutionary music of the end of the twentieth century and early twenty first century. Born in 1939 in the period of fascism and warfare, his life had been dominated by the experiences of Sharpeville, police brutality, racism , exploitation and resistance. In response, he sought avenues for self expression and articulation and up to the very end he was critical of the way in which the top leadership of the African National Congress had capitulated before international capital. In our discussion he shared the regrets that Bishop Trevor Huddleston had expressed over the compromises made by the liberation movements in seeking to enter the corridors of power in Pretoria.

Masekela felt strongly about the looting spree that had been undertaken by sections of the leadership of the African National Congress under the banner of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). In many ways, his salvation had come from his immersion in the anti racist struggles in North America, and his internship with the greats of African American jazz leaders. Hence, there had been no compromise by Masekela when the political leaders embraced neo-liberalism to justify their own primitive accumulation of capital. He could rub shoulders with dignitaries but he never forgot where he came from. All over the world leaders sought his music and his performance before the Queen and Nelson Mandela at the Royal Albert Hall in 1996 showed his irreverence before pomp and piety when he danced in the Royal box.

Hugh Masekela had left South Africa soon after the Sharpeville massacres but he never forgot the conditions of oppression of the working peoples. His autobiography Still Grazing: The Musical Journey provides a clear statement of his internationalism and his commitment to the rights of oppressed peoples whether in Watts, California 1965, in Nigeria with Feli Ransome Kuti or in the jazz centers of the world with greats such as Dizzy Gillespie . It was the struggles of the working poor that fired him up and the song ‘Stimela’ that was released in 1994 remains one of the better tributes to the solidarity of mine workers all over Southern Africa. In a period when the chauvinism of the current political leaders of government in South Africa rendered them silent on the xenophobia that has swept the society, Masekela used this song at numerous concerts and performances to remind the working peoples that the tasks of emancipation were incomplete.

During the era of apartheid repression and collaboration between the US government and the racist regime in South Africa, Masekela remained in the vanguard of the movement and made numerous songs to defy the barbarism of racist capitalism. When the South African government had launched its Total Strategy to destroy the liberation movements, Masekela released the song “Bring Him Back Home”. In the period of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, the racists had decided that Nelson Mandela would die in jail and that the liberation movements would be crushed. The song calling for the release of Mandela pushed forward the sanctions campaign and the Free Mandela campaigns at a crucial moment in the history of the anti-apartheid struggles.

By 1989 after the military defeat of the South African armed forces at Cuito Cuanavale, Masekela relocated to South Africa in 1990 and immersed himself into the lively jazz scene that had sustained the spirits of the peoples all through the terrorism of apartheid. As a member and strong supporter of the Cultural Reclamation Forum, a group of progressive literary, visual and musical artists and cultural workers based in Johannesburg, Masekela’s voice gave guidance and inspiration to many discussions and specific programs held to provide focus during the turbulent period of new state construction.

The sentiments and ideas of freedom that he promoted were on full display when Masekela acted as a node for the progressive artists and musicians who had come forward for the African Union concert held at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on 9th July, 2002, The cultural artists brought the songs of peace before a large audience (live and via radio, television and internet). A group going by the name of Joyous Celebration brought together the voices of all races in South Africa to provide inspirational music for the ongoing struggles to transcend the heritage of apartheid in South Africa and by extension, global apartheid. The artist Lagbaja from Nigeria echoed the cries for peace and justice. Performing in a mask, this artist declared that his face would not be shown in a performance until all of the ordinary workers in Africa have justice.

In the Yoruba language (Nigeria), Lagbaja means variously somebody, anybody, everybody and nobody in particular. It is a specific reference to the loss of identity of African peoples and Lagbaja sang on behalf of the faceless Africans in all parts of the world.

Another singer, Letta Mbulu, brought out the songs of peace and love of African women. Functioning as a cultural artist and as the UNICEF representative in Southern Africa she served a representative for peace and unity and seeks to mobilize oppressed women as the powerful forces of peace. Oliver Mtukudzi, the Zimbabwean singer, is a musician and lyricist singing songs of liberation since 1977. Fifteen years ago he worked with Masekela as cultural artists opposing the brutality and repression of the Zimbabwean government. In his rendition of the song, “What are we going to do?,” one African activist noted that this call was the twenty first century rendition of Lenin’s, What is to be Done?

The power of this call for new politics and new mobilization was reflected in the reality that the cultural artists were using all of the communications media of the twenty first century to speak in all of the languages calling for peace. While singing in Shona and Ndebele (languages of Zimbabwe), Tuku (as Mtukudzi is called) was communicating to the young and the old and asserting the claim that the cultural artists was offering a different kind of leadership.

This message was underlined by the anchor of the evening – Hugh Masekela. It was in this setting that Masekela brought together his tremendous international experience as trumpeter, bandleader, composer and lyricist. On this occasion, Masekela understood that he was now reaching another generation different from the era of John Coltrane and Janis Joplin. He did not disappoint.

At the launch of the African Union Masakela was at the forefront of composing the theme song for this continental representative organization. The song that underlined the depth of the feeling of the mass of the people of Africa was the song entitled, “Everything Must Change.” This was a song calling on all of the old leaders such as Eyadema of Togo, Moi of Kenya and Mugabe of Zimbabwe to step down. Masekela drew attention to the destructiveness of the militarists such as Jonas Savimbi and the militarists in Liberia and called on the African youths to struggle for peace.

The songs “Change” and “Stimela” sent a clear message to leaders such as Thabo Mbeki who had become an apologist for ‘nationalists’ such as Mugabe. Whether it was in Ghana, New York or Johannesburg, freedom lovers will this week join in the celebration of the contribution of Hugh Masekela

Rest well freedom fighter your music will continue to inspire those who have never surrendered.

Hugh Masekela: No Room for Compromise

It was less than a year ago on March 15, 2017 when I sat down with Hugh in Sandton to talk about his support and participation in the second Kwame Nkrumah Cultural and Intellectual Festival. I had contacted Hugh through our mutual cultural worker friends to request that he participate in the Festival that was scheduled for June 25, 2017. In the communication, Hugh had expressed an interest in coming to the public lecture that I was scheduled to deliver on March 14 at the University of Johannesburg. Before the lecture he had sent his regrets that he could not come to the lecture but dispatched Rapelang Leeuw to collect me so that he could discuss his contribution to this festival.

The theme of the Festival was Education for Transformation.

From the outset of the discussion, Hugh Masekela made it clear that he supported the idea of the Festival, and that he would travel to Legon, Ghana and perform at his own expense. After explaining the nature of the enterprise to promote the ideas of Kwame Nkrumah for a free, emancipated and socialist Africa, Hugh called up Mbongeni Ngema (composer and director of Sarafina fame) to discuss how the Sarafina expression of defiance could enhance the festival. After brainstorming for two hours of how much it would cost to bring the group of over 70 performers to Ghana, we agreed that we would look for sponsors and to see the availability of the Ghana National Theatre for their performance in Accra.

Hugh was excited about his planned trip to the USA in May 2017 to promote his new album of 2016, No Borders. I left Johannesburg with the optimism that Masekela had fired up in his enthusiastic support for this new push for African Unity and for politically educating the youths about the tasks ahead. In May when I contacted the manager to discuss the logistics of his participation in the Festival, we were informed that Hugh would not be well enough to perform. We did not then know that Hugh would never perform again. Hugh fought a long battle with prostrate cancer and joined the ancestors on January 23, 2018.

For over 60 years Hugh had been at the forefront of world revolutionary trends and made his mark at the site of the global anti racist struggles. It was fifty years ago in the midst of the ‘68 uprisings when Masekela used his trumpet to inspire the youths who were then fighting for revolutionary change all over the world. His album and the lead song, Grazing in the Grass, was a song of inspiration. His sounds of struggle, inspiration, revolutionary change and love are now part of the history of revolutionary music of the end of the twentieth century and early twenty first century. Born in 1939 in the period of fascism and warfare, his life had been dominated by the experiences of Sharpeville, police brutality, racism , exploitation and resistance. In response, he sought avenues for self expression and articulation and up to the very end he was critical of the way in which the top leadership of the African National Congress had capitulated before international capital. In our discussion he shared the regrets that Bishop Trevor Huddleston had expressed over the compromises made by the liberation movements in seeking to enter the corridors of power in Pretoria.

Masekela felt strongly about the looting spree that had been undertaken by sections of the leadership of the African National Congress under the banner of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). In many ways, his salvation had come from his immersion in the anti racist struggles in North America, and his internship with the greats of African American jazz leaders. Hence, there had been no compromise by Masekela when the political leaders embraced neo-liberalism to justify their own primitive accumulation of capital. He could rub shoulders with dignitaries but he never forgot where he came from. All over the world leaders sought his music and his performance before the Queen and Nelson Mandela at the Royal Albert Hall in 1996 showed his irreverence before pomp and piety when he danced in the Royal box.

Hugh Masekela had left South Africa soon after the Sharpeville massacres but he never forgot the conditions of oppression of the working peoples. His autobiography Still Grazing: The Musical Journey provides a clear statement of his internationalism and his commitment to the rights of oppressed peoples whether in Watts, California 1965, in Nigeria with Feli Ransome Kuti or in the jazz centers of the world with greats such as Dizzy Gillespie . It was the struggles of the working poor that fired him up and the song ‘Stimela’ that was released in 1994 remains one of the better tributes to the solidarity of mine workers all over Southern Africa. In a period when the chauvinism of the current political leaders of government in South Africa rendered them silent on the xenophobia that has swept the society, Masekela used this song at numerous concerts and performances to remind the working peoples that the tasks of emancipation were incomplete.

During the era of apartheid repression and collaboration between the US government and the racist regime in South Africa, Masekela remained in the vanguard of the movement and made numerous songs to defy the barbarism of racist capitalism. When the South African government had launched its Total Strategy to destroy the liberation movements, Masekela released the song “Bring Him Back Home”. In the period of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, the racists had decided that Nelson Mandela would die in jail and that the liberation movements would be crushed. The song calling for the release of Mandela pushed forward the sanctions campaign and the Free Mandela campaigns at a crucial moment in the history of the anti-apartheid struggles.

By 1989 after the military defeat of the South African armed forces at Cuito Cuanavale, Masekela relocated to South Africa in 1990 and immersed himself into the lively jazz scene that had sustained the spirits of the peoples all through the terrorism of apartheid. As a member and strong supporter of the Cultural Reclamation Forum, a group of progressive literary, visual and musical artists and cultural workers based in Johannesburg, Masekela’s voice gave guidance and inspiration to many discussions and specific programs held to provide focus during the turbulent period of new state construction.

The sentiments and ideas of freedom that he promoted were on full display when Masekela acted as a node for the progressive artists and musicians who had come forward for the African Union concert held at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on 9th July, 2002, The cultural artists brought the songs of peace before a large audience (live and via radio, television and internet). A group going by the name of Joyous Celebration brought together the voices of all races in South Africa to provide inspirational music for the ongoing struggles to transcend the heritage of apartheid in South Africa and by extension, global apartheid. The artist Lagbaja from Nigeria echoed the cries for peace and justice. Performing in a mask, this artist declared that his face would not be shown in a performance until all of the ordinary workers in Africa have justice.

In the Yoruba language (Nigeria), Lagbaja means variously somebody, anybody, everybody and nobody in particular. It is a specific reference to the loss of identity of African peoples and Lagbaja sang on behalf of the faceless Africans in all parts of the world.

Another singer, Letta Mbulu, brought out the songs of peace and love of African women. Functioning as a cultural artist and as the UNICEF representative in Southern Africa she served a representative for peace and unity and seeks to mobilize oppressed women as the powerful forces of peace. Oliver Mtukudzi, the Zimbabwean singer, is a musician and lyricist singing songs of liberation since 1977. Fifteen years ago he worked with Masekela as cultural artists opposing the brutality and repression of the Zimbabwean government. In his rendition of the song, “What are we going to do?,” one African activist noted that this call was the twenty first century rendition of Lenin’s, What is to be Done?

The power of this call for new politics and new mobilization was reflected in the reality that the cultural artists were using all of the communications media of the twenty first century to speak in all of the languages calling for peace. While singing in Shona and Ndebele (languages of Zimbabwe), Tuku (as Mtukudzi is called) was communicating to the young and the old and asserting the claim that the cultural artists was offering a different kind of leadership.

This message was underlined by the anchor of the evening – Hugh Masekela. It was in this setting that Masekela brought together his tremendous international experience as trumpeter, bandleader, composer and lyricist. On this occasion, Masekela understood that he was now reaching another generation different from the era of John Coltrane and Janis Joplin. He did not disappoint.

At the launch of the African Union Masakela was at the forefront of composing the theme song for this continental representative organization. The song that underlined the depth of the feeling of the mass of the people of Africa was the song entitled, “Everything Must Change.” This was a song calling on all of the old leaders such as Eyadema of Togo, Moi of Kenya and Mugabe of Zimbabwe to step down. Masekela drew attention to the destructiveness of the militarists such as Jonas Savimbi and the militarists in Liberia and called on the African youths to struggle for peace.

The songs “Change” and “Stimela” sent a clear message to leaders such as Thabo Mbeki who had become an apologist for ‘nationalists’ such as Mugabe. Whether it was in Ghana, New York or Johannesburg, freedom lovers will this week join in the celebration of the contribution of Hugh Masekela

Rest well freedom fighter your music will continue to inspire those who have never surrendered.

More articles by:Horace G. Campbell

Horace Campbell is Professor of African American Studies and Political Science, Syracuse University. He is the author of Global NATO and the Catastrophic Failure in Libya, Monthly Review Press, 2013.

Notes.

Labels:

CounterPunch,

Horace G Campbell,

Hugh Masekela

24 January 2018

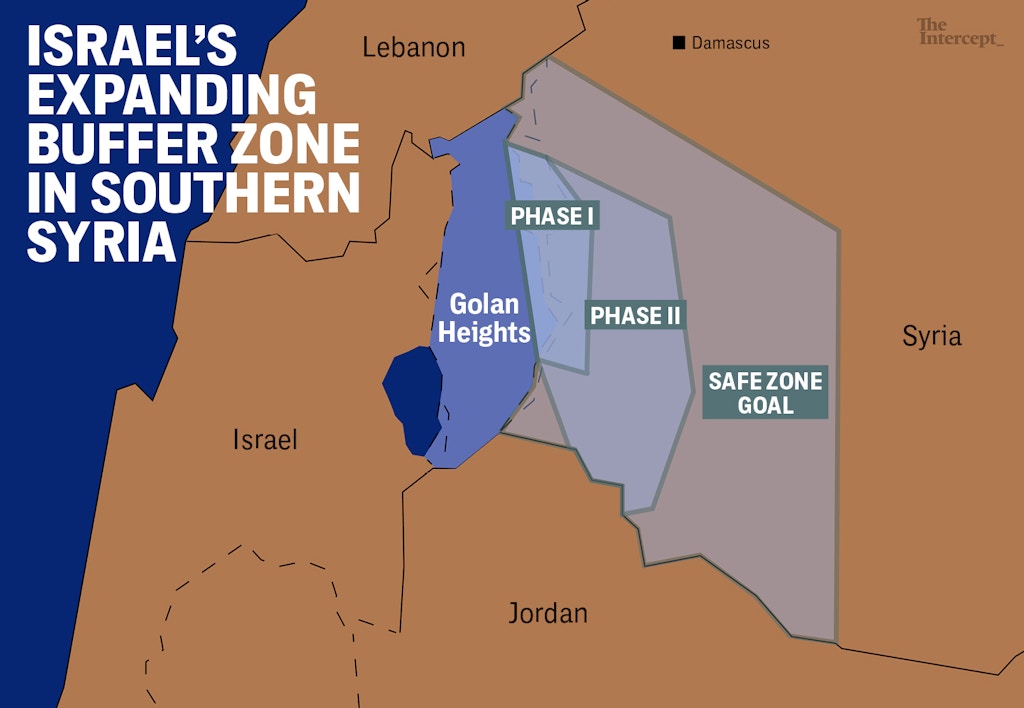

ISRAEL'S "SAFE ZONE" IS CREEPING FURTHER INTO SYRIA

Israel is expanding

its influence and control deeper into opposition-held southern Syria,

according to multiple sources in the area. After failed attempts to

ensure its interests were safeguarded by the major players in the war

next door, Israel is pushing to implement the second phase of its

“safe-zone” project — an attempt to expand a buffer ranging out from the

occupied Golan Heights deeper into the southern Syrian provinces of

Quneitra and Daraa. The safe zone expansion marks a move toward deeper

Israeli involvement in Syria’s civil war.

The Intercept learned the outlines of the safe-zone expansion plan through a monthslong investigation relying on information from a variety of sources, including Syrian opposition activists on the ground in the south, Syrian opposition figures based in Jordan, Syrian government sources, and an Israeli-American NGO directly involved in the safe-zone project.

The safe zone appears intended to keep the Syrian army and its Iranian and Lebanese allies as far away from Israel’s border as possible, as well as solidify Israel’s control over the occupied Golan Heights. Israel seized the Golan from Syria in 1967’s Six-Day War. Expanding a buffer zone would likely make any negotiations over the return of the Syrian territory more difficult in the future, because the Golan Heights will be surrounded on both sides by areas with significant Israeli influence.

Over the last two years, Israel started building out the first phase of a safe zone in southern Syria. The project enabled the Israeli army, through humanitarian organizations and military personnel, to gain access to opposition-held areas in return for supplying aid, medical treatment inside Israel, and basic goods.

According to sources, the second phase, which is currently underway, includes, among other things, the establishment of a 40-kilometer, Israeli-monitored buffer beyond the Golan Heights, a Syrian border police force armed and trained by Israel, and greater involvement in civil administration in opposition-controlled areas in two southern provinces. The expansion of the project also involves military aid to a wider array of opposition factions in both Quneitra and Daraa. The wider buffer zone also sees partnerships being built up with Syrian opposition leaders, civil society leaders, NGOs, and health officials on the ground to work on joint educational, health, and agricultural projects.

Israel has launched numerous strikes into Syrian territory, often understood to be efforts to keep advanced weapons out of the hands of hostile militants, like those in Lebanon’s Hezbollah. However, the buffer zone — and its expansion — stand as a deeper and more long-term investment in the Syrian war. Last summer, I reported on Israel’s burgeoning support for a rebel faction called the Golan Knights. Subsequently, rebels speaking to the Wall Street Journal confirmed that the cash payments, which Israel claimed were purely humanitarian, were used for paying fighters’ salaries and purchasing weapons and ammunition.

Contacted for comment about the safe-zone expansion by an Intercept journalist in New York, an Israeli official, who refused to speak under any other attribution, said, “It’s a ridiculous and unfounded claim, that Israel is creating a buffer zone. Israel provides humanitarian aid as part of its values and to help strengthen stability.” Confronted with previous reporting about Israeli support for Syrian rebel factions in the vicinity of the Golan Heights, the official refused to comment.

As the war drags on, more Syrians inside opposition areas are reluctantly accepting Israel’s influence and involvement in their communities. “The humanitarian situation here is hard,” explained Abu Omar, an opposition activist who lives in the rebel-held town of Quneitra and asked to not to have his full name used because of the sensitivity of the subject. Abu Omar said that initially people in the area were against Israeli involvement in the area. Though he still opposes Israel’s presence, he said, others have changed their minds: “When Israel gives people salaries, medication, food, and water, people start to like them, and honestly today, it is not a small number; it is a now a large number.”

“They bought people with aid,” he said. “Although not all the residents accept Israeli involvement.”

Over the summer, Israeli army and intelligence officials began implementing the second phase of the safe-zone project. They started to train and equip a force of around 500 Syrian opposition fighters from the Syrian rebel group, Golan Knights, as a border police force. The border guards, responsible for the border between the safe zone and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, would monitor the area and report back to the Israelis, according to a Syrian opposition source in the area and Syrian government sources monitoring the area, neither of whom agreed to be quoted on the record because of the sensitivity of the issue.

The border force is expected to patrol the separation fence from just south of the government-allied Druze town of Hadar through opposition-controlled towns of Jabata Khashab, Bir Ajam, Hamadiyah, and Quneitra, eventually crossing all the way to Rafid in southern Quneitra province.

“This is a fully-fledged Israeli project, where they are pouring money and time to make it happen,” said Abu Ahmad, the pseudonym of an opposition activist based in Jabata Khashab — the same town where the Golan Knights are based.

Abu Ahmad declined to use his real name because of the sensitivity of the issue. “They’ve been provided with M16s” — American-made assault rifles used by the Israelis — “vehicles, salaries, and training.”

The Golan Knights have a military base located no more than a few hundred meters from the border in opposition-controlled territory, making it relatively easy for Israeli personnel to access.

Some locals are not pleased with this development. “What Israel is doing now in the area is very real and very dangerous for the future here,” said Abu Ahmad, who fears Israel’s activities will be to the detriment of Syria and Syrians, citing Israel’s 22-year occupation of southern Lebanon as a precedent.

A picture taken on Nov. 20, 2017, shows Israeli Merkava Mk-IV tanks taking part in a military exercise near the border with Syria in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

Israel’s recent anxieties about the Syrian civil war spring

from a flurry of activity over the summer that saw the implementation of

a U.S.-Jordanian-Russian de-escalation deal, the announcement of the

termination of the CIA-backed train-and-equip program for rebels, and

the significant reduction of Jordanian support for opposition groups

fighting the Syrian government.

Israel has both publicly and privately voiced its concerns over what it sees as increasing Iranian influence in Syria and Hezbollah’s presence close to its northern border. But Israel feels its worries have not been adequately addressed, remaining unsatisfied with the guarantees it has received thus far — especially after repeated visits by its political and intelligence leaders to Washington and Moscow, where they were unable to secure any concrete promises from their allies.

According to a Western diplomatic source, who asked not to be identified because he is not permitted to speak to the media, Israeli officials have been pushing for the implementation of a 40-kilometer safe zone in the south, calling on European countries to support this idea, and asking the U.S. and Russia for guarantees of its implementation. While both the U.S. and Russia told Israeli officials they care about the country’s safety, the request for the 40-kilometer safe zone has all but been rejected, according to Western diplomats, who were not authorized to speak to the media

However, Israeli army’s chief of staff, Gadi Eisenkot made it clear that Israel is still seeking to implement a 40-kilometer-wide zone free of any Iranian influence. “We’re pursuing several different avenues to prevent Iranian entrenchment within 30-40km of the border,” he told an Israeli newspaper. “We want to get to a point where there is no Iranian influence in Syria, and this is being done in a combined military and diplomatic effort.” A zone of that size would stretch across both the Quneitra and Daraa provinces.

According to Syrian opposition commanders based in Jordan, who have been privy to the details of the de-escalation deal, the Israelis made it clear that even 40 kilometers would not be enough.

“They basically want Hezbollah and Iran to be pushed as far back as Hama,” said one commander based in Amman, who asked not to be named because of the delicacy of the issue.

Recently, Israeli concern about Iranian and Hezbollah presence in the area was exacerbated after it was revealed that Russia and the U.S. plan on maintaining the status quo regarding the de-escalation deal in the south, with Israeli reports citing the Russian defense minister as having told the Israelis that 40 kilometers is unrealistic.

Israeli concerns have been further heightened following a government-led offensive last month that resulted in the surrender of opposition-held Beit Jinn — which borders the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights — bringing government forces and its allies closer to the Israeli-held territory.

It’s not just Iran and its allied forces in Lebanon that Israel is concerned about, however, but also its control over the Golan Heights. Israel captured the 1,200-square-kilometer territory of land in 1967 and has occupied it since. Unlike the other territories it occupies, Israel officially annexed the Golan Heights in 1981 in a move condemned by the international community. While Israel has spent decades seeking international legitimacy for its claim, only in the last five years — with the Syrian Civil War at its doorstep — have these calls for international recognition of the Golan as Israeli territory become louder and more prevalent in its political and diplomatic circles.

The extended buffer zone, or “safe zone” inside Syria, would bolster the Israeli stance that the Syrian government is not in a position to make claims of sovereignty over an area that is not even under Damascus’s control.

The push into Syrian territory is being done in tandem with an increase in Israeli activity inside the occupied Golan Heights. The push includes expanding Israeli settlement activity; investing more in local infrastructure and the local economy; encouraging the 20,000 Syrians still living there to take Israeli citizenship and participate in local elections; and the licensing and approval of a controversial multimillion-dollar oil exploration project — all toward the aim of cementing Israel’s hold on the Golan Heights.

In this April 6, 2017, photo made in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, Israeli military medics assist wounded Syrians.

With opposition factions now searching for new sponsors after

their previous sponsors — Jordan, through its Military Operations

Command, and the United States — shifted their Syria policies, Israel

has jumped at the chance to step in.

In late July, a small group of Israeli military and intelligence personnel, traveling in ambulances, made a tour of the west Daraa countryside, according to Syrian government military sources, who asked not to be named because they are not permitted to speak to the media. During their tour, the Israeli officials met with commanders from the nationalist rebel group Liwa Jaydour, which is linked to the loose coalition of the Free Syrian Army, as well as Jaysh al-Ababil, which operates under the umbrella of the Jordanian- and American-backed rebel coalition, known as the Southern Front.

Another meeting then took place in September in the Quneitra border town of Rafid, where local council leaders, doctors, and militia commanders — including those from Liwa Jaydour, the Golan Knights, and the Syrian Revolutionaries Front — met with an Israeli representative to discuss further cooperation.

“There are some from the Southern Front who are now working with Israel, and the same for Free Syrian Army factions, taking money and weapons,” said Abu Ahmad, the opposition activist. “Jordan stopped sending them weapons, so they turned to Israel instead.”

Israel’s reach into the borderlands is beginning to be become publicly evident. A video recently released by SMART news agency showed a Daraa-based group, Ahrar Nawa Division, which is linked to the Free Syrian Army, using rockets from Israel.

Several senior commanders within the Southern Front based in Jordan and Syrian opposition activists in Quneitra confirmed to The Intercept that Liwa Jaydour, Liwa Saif al-Sham and Jaysh al-Ababil are now receiving aid from the Israelis.

“Yes, they are receiving some level of aid from Israel, and so are other groups, especially those within the Syrian Revolutionaries Front” — a loose coalition of other rebel factions — “who are now completely in Israel’s pocket,” said one Amman-based commander, who spoke on condition of anonymity for security reasons. “And we are starting to see Israeli aid coming through to Daraa, too.”

“There is enough aid,” he said, “but it is because the people are poor and when you offer them something they won’t turn it down.”

A metal placard in the shape of an Israeli soldier stands on an old bunker as the moon rises over Syria, as seen from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, on Monday, Nov. 14, 2016.

Keen to emulate the success that Turkey

has had in cementing its long-term influence through opposition proxies

in the areas along its border, Israel is attempting to do the same in

Syria’s south — not just through armed groups, but also by working

closely with local councils on health, security, infrastructure, and

education issues.

Amaliah, an Israeli NGO founded by Israeli-American businessman Moti Kahana, has been involved in Quneitra, in the nominal United Nations buffer zone between the Israeli-occupied Golan and Syrian-controlled territory, since 2016.

The group is now working with local partners in Daraa, looking to expand its safe-zone mission further into Syria. While most of Amaliah’s projects are based in the south, Kahana said he’s no stranger to Syria’s opposition-controlled north. Recent media reports have featured Amaliah because of its involvement in the establishment of a school in the opposition-held northern city of Idlib.

“When I started helping Syrians by the end of 2011, I started in Idlib,” Kahana said. “It took a long time for [my role] to be publicly acknowledged in the north. No one wanted to be affiliated with an Israeli.”

When the news about the school broke, opposition activists in Idlib denied any Israeli involvement in the area, and the school itself also contacted Kahana asking him to deny any involvement, he said. “They were scared because of Nusra’s reaction, as Nusra controls the area,” said Kahana, referring to the Nursa Front, a jihadi Syrian rebel group. “Now [the school is] asking me to say I’m involved, with the hopes this will stop the Russian bombing in the area.”

Meanwhile in the south, Amaliah, in partnership with the Israeli authorities, has been able to work with local opposition councils relatively unhindered, leading to what Kahana describes as the successful implementation and completion of “phase one” of the buffer zone — a 10-kilometer-wide area in Syrian territory where Israeli NGOs and military personnel can operate.

“In the south it’s much easier,” said Kahana. “I get lists from inside, and also the Israelis come to me with requests. That’s a little easier for me because the Israelis are involved, and they know the people, they’re already talking to them.

Even if I get the list from inside, I still run it by the Israelis because they know what’s going on.”

Now Israel is busy working on the implementation of the second phase of the safe zone with the expansion into Daraa, Kahana said.

“I can say yes,” Kahana said when asked about the buffer expansion. “There were some political issues, because Daraa was difficult to partner with the Israelis,” he added, citing historical grievances and animosity toward Israel as the main obstacle for opposition groups and civilians residing in the southwestern province. “It was a little bit harder for them to accept supplies through the Israeli border and to even work with the Israelis, but I told the groups there to look at what we did with stage one of the safe zone and its success.”

Kahana said he had a working relationship with several of the local opposition groups in Daraa, as well as local NGOs, such as Rahma Relief, and local doctors on the ground.

“By 2018, I want to establish two schools, one in Daraa and one in Quneitra, as well as have a hospital inside Quneitra up and running,” Kahana said, adding that the hospital will be in partnership with Syrian American Medical Society, one of the leading Syrian-American NGOs working in opposition areas. “I’ve already started my due diligence in the area.”

The Intercept learned the outlines of the safe-zone expansion plan through a monthslong investigation relying on information from a variety of sources, including Syrian opposition activists on the ground in the south, Syrian opposition figures based in Jordan, Syrian government sources, and an Israeli-American NGO directly involved in the safe-zone project.

The safe zone appears intended to keep the Syrian army and its Iranian and Lebanese allies as far away from Israel’s border as possible, as well as solidify Israel’s control over the occupied Golan Heights. Israel seized the Golan from Syria in 1967’s Six-Day War. Expanding a buffer zone would likely make any negotiations over the return of the Syrian territory more difficult in the future, because the Golan Heights will be surrounded on both sides by areas with significant Israeli influence.

Over the last two years, Israel started building out the first phase of a safe zone in southern Syria. The project enabled the Israeli army, through humanitarian organizations and military personnel, to gain access to opposition-held areas in return for supplying aid, medical treatment inside Israel, and basic goods.

According to sources, the second phase, which is currently underway, includes, among other things, the establishment of a 40-kilometer, Israeli-monitored buffer beyond the Golan Heights, a Syrian border police force armed and trained by Israel, and greater involvement in civil administration in opposition-controlled areas in two southern provinces. The expansion of the project also involves military aid to a wider array of opposition factions in both Quneitra and Daraa. The wider buffer zone also sees partnerships being built up with Syrian opposition leaders, civil society leaders, NGOs, and health officials on the ground to work on joint educational, health, and agricultural projects.

Israel has launched numerous strikes into Syrian territory, often understood to be efforts to keep advanced weapons out of the hands of hostile militants, like those in Lebanon’s Hezbollah. However, the buffer zone — and its expansion — stand as a deeper and more long-term investment in the Syrian war. Last summer, I reported on Israel’s burgeoning support for a rebel faction called the Golan Knights. Subsequently, rebels speaking to the Wall Street Journal confirmed that the cash payments, which Israel claimed were purely humanitarian, were used for paying fighters’ salaries and purchasing weapons and ammunition.

Contacted for comment about the safe-zone expansion by an Intercept journalist in New York, an Israeli official, who refused to speak under any other attribution, said, “It’s a ridiculous and unfounded claim, that Israel is creating a buffer zone. Israel provides humanitarian aid as part of its values and to help strengthen stability.” Confronted with previous reporting about Israeli support for Syrian rebel factions in the vicinity of the Golan Heights, the official refused to comment.

As the war drags on, more Syrians inside opposition areas are reluctantly accepting Israel’s influence and involvement in their communities. “The humanitarian situation here is hard,” explained Abu Omar, an opposition activist who lives in the rebel-held town of Quneitra and asked to not to have his full name used because of the sensitivity of the subject. Abu Omar said that initially people in the area were against Israeli involvement in the area. Though he still opposes Israel’s presence, he said, others have changed their minds: “When Israel gives people salaries, medication, food, and water, people start to like them, and honestly today, it is not a small number; it is a now a large number.”

“They bought people with aid,” he said. “Although not all the residents accept Israeli involvement.”

Over the summer, Israeli army and intelligence officials began implementing the second phase of the safe-zone project. They started to train and equip a force of around 500 Syrian opposition fighters from the Syrian rebel group, Golan Knights, as a border police force. The border guards, responsible for the border between the safe zone and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, would monitor the area and report back to the Israelis, according to a Syrian opposition source in the area and Syrian government sources monitoring the area, neither of whom agreed to be quoted on the record because of the sensitivity of the issue.

The border force is expected to patrol the separation fence from just south of the government-allied Druze town of Hadar through opposition-controlled towns of Jabata Khashab, Bir Ajam, Hamadiyah, and Quneitra, eventually crossing all the way to Rafid in southern Quneitra province.

“This is a fully-fledged Israeli project, where they are pouring money and time to make it happen,” said Abu Ahmad, the pseudonym of an opposition activist based in Jabata Khashab — the same town where the Golan Knights are based.

Abu Ahmad declined to use his real name because of the sensitivity of the issue. “They’ve been provided with M16s” — American-made assault rifles used by the Israelis — “vehicles, salaries, and training.”

The Golan Knights have a military base located no more than a few hundred meters from the border in opposition-controlled territory, making it relatively easy for Israeli personnel to access.

Some locals are not pleased with this development. “What Israel is doing now in the area is very real and very dangerous for the future here,” said Abu Ahmad, who fears Israel’s activities will be to the detriment of Syria and Syrians, citing Israel’s 22-year occupation of southern Lebanon as a precedent.

A picture taken on Nov. 20, 2017, shows Israeli Merkava Mk-IV tanks taking part in a military exercise near the border with Syria in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

Photo: Jalaa Marey/AFP/Getty Images

Israel has both publicly and privately voiced its concerns over what it sees as increasing Iranian influence in Syria and Hezbollah’s presence close to its northern border. But Israel feels its worries have not been adequately addressed, remaining unsatisfied with the guarantees it has received thus far — especially after repeated visits by its political and intelligence leaders to Washington and Moscow, where they were unable to secure any concrete promises from their allies.

According to a Western diplomatic source, who asked not to be identified because he is not permitted to speak to the media, Israeli officials have been pushing for the implementation of a 40-kilometer safe zone in the south, calling on European countries to support this idea, and asking the U.S. and Russia for guarantees of its implementation. While both the U.S. and Russia told Israeli officials they care about the country’s safety, the request for the 40-kilometer safe zone has all but been rejected, according to Western diplomats, who were not authorized to speak to the media

However, Israeli army’s chief of staff, Gadi Eisenkot made it clear that Israel is still seeking to implement a 40-kilometer-wide zone free of any Iranian influence. “We’re pursuing several different avenues to prevent Iranian entrenchment within 30-40km of the border,” he told an Israeli newspaper. “We want to get to a point where there is no Iranian influence in Syria, and this is being done in a combined military and diplomatic effort.” A zone of that size would stretch across both the Quneitra and Daraa provinces.

According to Syrian opposition commanders based in Jordan, who have been privy to the details of the de-escalation deal, the Israelis made it clear that even 40 kilometers would not be enough.

“They basically want Hezbollah and Iran to be pushed as far back as Hama,” said one commander based in Amman, who asked not to be named because of the delicacy of the issue.

Recently, Israeli concern about Iranian and Hezbollah presence in the area was exacerbated after it was revealed that Russia and the U.S. plan on maintaining the status quo regarding the de-escalation deal in the south, with Israeli reports citing the Russian defense minister as having told the Israelis that 40 kilometers is unrealistic.

Israeli concerns have been further heightened following a government-led offensive last month that resulted in the surrender of opposition-held Beit Jinn — which borders the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights — bringing government forces and its allies closer to the Israeli-held territory.

It’s not just Iran and its allied forces in Lebanon that Israel is concerned about, however, but also its control over the Golan Heights. Israel captured the 1,200-square-kilometer territory of land in 1967 and has occupied it since. Unlike the other territories it occupies, Israel officially annexed the Golan Heights in 1981 in a move condemned by the international community. While Israel has spent decades seeking international legitimacy for its claim, only in the last five years — with the Syrian Civil War at its doorstep — have these calls for international recognition of the Golan as Israeli territory become louder and more prevalent in its political and diplomatic circles.

The extended buffer zone, or “safe zone” inside Syria, would bolster the Israeli stance that the Syrian government is not in a position to make claims of sovereignty over an area that is not even under Damascus’s control.

The push into Syrian territory is being done in tandem with an increase in Israeli activity inside the occupied Golan Heights. The push includes expanding Israeli settlement activity; investing more in local infrastructure and the local economy; encouraging the 20,000 Syrians still living there to take Israeli citizenship and participate in local elections; and the licensing and approval of a controversial multimillion-dollar oil exploration project — all toward the aim of cementing Israel’s hold on the Golan Heights.

In this April 6, 2017, photo made in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, Israeli military medics assist wounded Syrians.

Photo: Dusan Vranic/AP

In late July, a small group of Israeli military and intelligence personnel, traveling in ambulances, made a tour of the west Daraa countryside, according to Syrian government military sources, who asked not to be named because they are not permitted to speak to the media. During their tour, the Israeli officials met with commanders from the nationalist rebel group Liwa Jaydour, which is linked to the loose coalition of the Free Syrian Army, as well as Jaysh al-Ababil, which operates under the umbrella of the Jordanian- and American-backed rebel coalition, known as the Southern Front.

Another meeting then took place in September in the Quneitra border town of Rafid, where local council leaders, doctors, and militia commanders — including those from Liwa Jaydour, the Golan Knights, and the Syrian Revolutionaries Front — met with an Israeli representative to discuss further cooperation.

“There are some from the Southern Front who are now working with Israel, and the same for Free Syrian Army factions, taking money and weapons,” said Abu Ahmad, the opposition activist. “Jordan stopped sending them weapons, so they turned to Israel instead.”

Israel’s reach into the borderlands is beginning to be become publicly evident. A video recently released by SMART news agency showed a Daraa-based group, Ahrar Nawa Division, which is linked to the Free Syrian Army, using rockets from Israel.

Several senior commanders within the Southern Front based in Jordan and Syrian opposition activists in Quneitra confirmed to The Intercept that Liwa Jaydour, Liwa Saif al-Sham and Jaysh al-Ababil are now receiving aid from the Israelis.

“Yes, they are receiving some level of aid from Israel, and so are other groups, especially those within the Syrian Revolutionaries Front” — a loose coalition of other rebel factions — “who are now completely in Israel’s pocket,” said one Amman-based commander, who spoke on condition of anonymity for security reasons. “And we are starting to see Israeli aid coming through to Daraa, too.”

“There is enough aid,” he said, “but it is because the people are poor and when you offer them something they won’t turn it down.”

A metal placard in the shape of an Israeli soldier stands on an old bunker as the moon rises over Syria, as seen from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, on Monday, Nov. 14, 2016.

Photo: Ariel Schalit/AP

Amaliah, an Israeli NGO founded by Israeli-American businessman Moti Kahana, has been involved in Quneitra, in the nominal United Nations buffer zone between the Israeli-occupied Golan and Syrian-controlled territory, since 2016.

The group is now working with local partners in Daraa, looking to expand its safe-zone mission further into Syria. While most of Amaliah’s projects are based in the south, Kahana said he’s no stranger to Syria’s opposition-controlled north. Recent media reports have featured Amaliah because of its involvement in the establishment of a school in the opposition-held northern city of Idlib.

“When I started helping Syrians by the end of 2011, I started in Idlib,” Kahana said. “It took a long time for [my role] to be publicly acknowledged in the north. No one wanted to be affiliated with an Israeli.”

When the news about the school broke, opposition activists in Idlib denied any Israeli involvement in the area, and the school itself also contacted Kahana asking him to deny any involvement, he said. “They were scared because of Nusra’s reaction, as Nusra controls the area,” said Kahana, referring to the Nursa Front, a jihadi Syrian rebel group. “Now [the school is] asking me to say I’m involved, with the hopes this will stop the Russian bombing in the area.”

Meanwhile in the south, Amaliah, in partnership with the Israeli authorities, has been able to work with local opposition councils relatively unhindered, leading to what Kahana describes as the successful implementation and completion of “phase one” of the buffer zone — a 10-kilometer-wide area in Syrian territory where Israeli NGOs and military personnel can operate.

“In the south it’s much easier,” said Kahana. “I get lists from inside, and also the Israelis come to me with requests. That’s a little easier for me because the Israelis are involved, and they know the people, they’re already talking to them.

Even if I get the list from inside, I still run it by the Israelis because they know what’s going on.”

Now Israel is busy working on the implementation of the second phase of the safe zone with the expansion into Daraa, Kahana said.

“I can say yes,” Kahana said when asked about the buffer expansion. “There were some political issues, because Daraa was difficult to partner with the Israelis,” he added, citing historical grievances and animosity toward Israel as the main obstacle for opposition groups and civilians residing in the southwestern province. “It was a little bit harder for them to accept supplies through the Israeli border and to even work with the Israelis, but I told the groups there to look at what we did with stage one of the safe zone and its success.”

Kahana said he had a working relationship with several of the local opposition groups in Daraa, as well as local NGOs, such as Rahma Relief, and local doctors on the ground.

“By 2018, I want to establish two schools, one in Daraa and one in Quneitra, as well as have a hospital inside Quneitra up and running,” Kahana said, adding that the hospital will be in partnership with Syrian American Medical Society, one of the leading Syrian-American NGOs working in opposition areas. “I’ve already started my due diligence in the area.”

Top photo: A Syrian military spokesperson, left,

points to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights on Dec. 23, 2017, in

Quneitra in southwestern Syria.

We depend on the support of readers like you to help keep our nonprofit newsroom strong and independent. Join Us

Labels:

Glenn Greenwald,

Golan Heights,

Iran Hezbollah,

Israel,

Syria,

The Intercept

20 January 2018

MISERY OF ISRAEL'S 38,000 AFRICAN ASYLUM SEEKERS - IN THE "ONLY DEMOCRACY IN THE MIDDLE EAST"!!

The misery of Israel’s 38,000 African asylum seekers and the dubious ‘third country’ solution

- KRISTEN VAN SCHIE

- Africa

- 19 Jan 2018 12:56 (South Africa)

61 Reactions

African asylum seekers living in Israel are

being asked to choose between deportation or prison as authorities in

that country crack down on “infiltrators”. But as several asylum seekers

tell KRISTEN VAN SCHIE, it’s no choice at all.

Muhtar Awdalla was given a choice: Leave Israel, or go to prison.

It was early 2014 and the Sudanese asylum seeker had already wasted months of his life behind bars – in Libya, in Egypt and, when he finally crossed the border, in Israel.

Having fled the conflict in Darfur as a teenager in 2003, the whole point of the years-long journey was to find a better life.

“There were so many people crossing to Israel,” Awdalla said. “They said the country really respected human life.”

But when he arrived there in 2009, he found the experience “opposite – totally opposite”.

For eight months he languished in a detention centre. It took months more to get a temporary visa – he couldn’t work without one. Even when he got it, he couldn’t study. Dreams of becoming a lawyer stagnated as his 20s ticked by in restaurant jobs and Hebrew classes and days and days spent queuing to renew his papers.

When the ultimatum of detention or deportation was put to Awdalla, the authorities proposed Uganda as his final destination. They would cover his flights and organise his travel documents. He would even get $3,500.

“I didn’t want to go to prison and waste my time again,” he said. “I thought if I went to Uganda, I could finally study.”

He caught a connecting flight though Jordan and at some point on the second leg of the journey fell asleep. He woke as the plane was landing. A sign from the window caught his eye: “Welcome to Khartoum Airport”. Israel had sent him back to Sudan.

“I was shocked and disappointed,” Awdalla said. “I never expected to survive. I thought the Sudanese government was going to kill me.”

He was promptly arrested and his belongings confiscated. They even took the $3,500.

***

It’s stories like Awdalla’s that send shivers down the spines of the estimated 38,000 African asylum seekers living in Israel, mostly from Eritrea and Sudan.

In December 2017, the country announced a new plan of forced deportations of asylum seekers to “third countries” in Africa, if those countries agree to take them.

The community will have to choose between leaving, or indefinite detention.

But the announcement is just the latest move in what activists describe as a sustained campaign by the Israeli government of “making life miserable” for asylum seekers to convince them to leave.

“They have no status here,” explained Dror Sadot, spokesperson for the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants NGO. “They’re not granted refugee status. The government calls them ‘infiltrators’. They pay taxes but are not granted any social rights... all of Israel’s responsibilities and obligations to asylum seekers are just thrown out.”

Testimony from asylum seekers who left voluntarily have named the “third countries” as Rwanda and Uganda, though both have denied the existence of any “written agreement” with Israel.

Sadot says voluntary deportees have arrived in Rwanda or Uganda with no legal documentation – “no work permit, no status, nothing”. Many are robbed of the $3,500 granted to them by the Israeli government or quickly trafficked out of the third countries to join the migration route through Libya to Europe.

“We can monitor only those people who survive. They tell us about their friends who died at sea, who drowned next to them.”

Like Awdalla, some say they were not sent to a third country at all, but to the very war zones they fled.

The deportations haven’t started yet and will not apply to families. But Sadot said the panic in the community is palpable.

“It’s really hard. I mean, people are standing here in a line outside our offices. We’re trying to calm the communities, to send messages out in their languages to explain the situation. We’re trying to see what legal options we have.”

***

Asylum seekers from Eritrea and Sudan first began arriving in Israel in the mid-2000s, before the country sealed off its border with Egypt.

After years under “group protection”, applications for refugee status in Israel opened in 2013.

Since then, only 11 people – 10 Eritreans and a Sudanese man – have applied successfully. The rest are deemed economic migrants and blamed for the crime rates in poorer Tel Aviv neighbourhoods.

Sudanese asylum seeker Anwar Suliman, 38, submitted his application more than four years ago.

“Until today, I didn’t get a yes or no,” he said. “It’s important for us to know the answer – it could change our lives.”

Speaking to Daily Maverick, Suliman detailed a frustrating life lived in the limbo of detention centres and visa application queues.

Back in Sudan, before he fled, he was an archaeologist, specialising in Egyptian and Sudanese history. His political activism twice landed him in jail.

“I had to escape. If I continued, I could get arrested even more. Maybe killed.”

Fifteen years later, Suliman now works in a restaurant in Tel Aviv. Altogether, he’s spent about two years in Israeli detention. It’s not a life, he says.

“But what can we do? Every year some new policy is coming...”

Still, given the choice between returning to Africa or a life behind bars, he would pick the latter.

“I miss Africa, but I’m not ready to go back,” he said. “Rwanda and Uganda are not my homeland.

“I don’t know what comes next. After what happened to us, you don’t have a plan any more. For some people life is clear. But for me nothing is clear.”

***

“It’s a racially motivated system,” Eritrean asylum seeker and community organiser Teklit Michael, 29, said.

After 10 years in Israel, he doesn’t mince his words. There were the people who supported the asylum seekers, “people who know about human dignity and human rights”. But they were in the minority, he said.

“Even the people who are issuing you visas, they treat you like shit, like a slave. They don’t give a shit. They don’t think that you’re a human being like them, that you can suffer, feel pain.”

In November 2017, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke glowingly of Africa on a visit to Kenya.

“We believe in the future of Africa, we love Africa and I would like very much not only to co-operate on an individual basis with each of your countries but also with the African Union,” he said.

But just three months earlier, he promised to return the Tel Aviv neighbourhoods where many Africans live “to the citizens of Israel”. Asylum seekers like Michael were “not refugees”, Netanyahu said, “but infiltrators looking for work”.

“They treat us like animals and blame us for everything,” Michael told Daily Maverick. “They never loved us. They never will love us.”

So why stay in a place that didn’t want him?

“I don’t have a choice. I don’t have a passport. I don’t have anything. I can’t go anywhere. And even if they give me the chance, I don’t know anything about Rwanda.”

Friends who had taken the deal were trafficked out of that country.

“Nobody actually stayed in Rwanda. Their documents are taken on arrival. They tell them to pay money for the hotel and money for the smugglers. Then they take them to the border.

“I don’t have any guarantee for my asylum claim, or for my protection. This is simply human trafficking.

“It’s better for me to stay here in prison than to go to Rwanda or Uganda.”

***

Muhtar did find his way to Uganda eventually – after a brother helped bribe him out of a Sudanese prison.

At 29, he’s now a third-year law student and president of his university’s law society.

“It’s an incredible feeling to finally be following my dreams,” he told Daily Maverick.

He misses Israel. He misses his friends there. But he plans on using his degree to sue the government for what it did to him.

“They lied to me. They took me to a place I didn’t want to go, a place that could have ended my life... If you don’t take risks in life, you will never succeed. But if I knew they were were going to send me to Sudan, I would never have taken that risk. Never.” DM

Photo: African asylum seekers and Israelis residents of South Tel Aviv neighborhoods hold signs in Hebrew that read 'South Tel Aviv is against the deportation' during a protest against the African migrants deportations in southern Tel Aviv, Israel, 09 January 2018. Some 38,000 African asylum seekers live in Israel. EPA-EFE/ABIR SULTAN

It was early 2014 and the Sudanese asylum seeker had already wasted months of his life behind bars – in Libya, in Egypt and, when he finally crossed the border, in Israel.

Having fled the conflict in Darfur as a teenager in 2003, the whole point of the years-long journey was to find a better life.

“There were so many people crossing to Israel,” Awdalla said. “They said the country really respected human life.”

But when he arrived there in 2009, he found the experience “opposite – totally opposite”.

For eight months he languished in a detention centre. It took months more to get a temporary visa – he couldn’t work without one. Even when he got it, he couldn’t study. Dreams of becoming a lawyer stagnated as his 20s ticked by in restaurant jobs and Hebrew classes and days and days spent queuing to renew his papers.

When the ultimatum of detention or deportation was put to Awdalla, the authorities proposed Uganda as his final destination. They would cover his flights and organise his travel documents. He would even get $3,500.

“I didn’t want to go to prison and waste my time again,” he said. “I thought if I went to Uganda, I could finally study.”

He caught a connecting flight though Jordan and at some point on the second leg of the journey fell asleep. He woke as the plane was landing. A sign from the window caught his eye: “Welcome to Khartoum Airport”. Israel had sent him back to Sudan.

“I was shocked and disappointed,” Awdalla said. “I never expected to survive. I thought the Sudanese government was going to kill me.”

He was promptly arrested and his belongings confiscated. They even took the $3,500.

***

It’s stories like Awdalla’s that send shivers down the spines of the estimated 38,000 African asylum seekers living in Israel, mostly from Eritrea and Sudan.

In December 2017, the country announced a new plan of forced deportations of asylum seekers to “third countries” in Africa, if those countries agree to take them.

The community will have to choose between leaving, or indefinite detention.

But the announcement is just the latest move in what activists describe as a sustained campaign by the Israeli government of “making life miserable” for asylum seekers to convince them to leave.

“They have no status here,” explained Dror Sadot, spokesperson for the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants NGO. “They’re not granted refugee status. The government calls them ‘infiltrators’. They pay taxes but are not granted any social rights... all of Israel’s responsibilities and obligations to asylum seekers are just thrown out.”

Testimony from asylum seekers who left voluntarily have named the “third countries” as Rwanda and Uganda, though both have denied the existence of any “written agreement” with Israel.

Sadot says voluntary deportees have arrived in Rwanda or Uganda with no legal documentation – “no work permit, no status, nothing”. Many are robbed of the $3,500 granted to them by the Israeli government or quickly trafficked out of the third countries to join the migration route through Libya to Europe.

“We can monitor only those people who survive. They tell us about their friends who died at sea, who drowned next to them.”

Like Awdalla, some say they were not sent to a third country at all, but to the very war zones they fled.

The deportations haven’t started yet and will not apply to families. But Sadot said the panic in the community is palpable.

“It’s really hard. I mean, people are standing here in a line outside our offices. We’re trying to calm the communities, to send messages out in their languages to explain the situation. We’re trying to see what legal options we have.”

***

Asylum seekers from Eritrea and Sudan first began arriving in Israel in the mid-2000s, before the country sealed off its border with Egypt.

After years under “group protection”, applications for refugee status in Israel opened in 2013.

Since then, only 11 people – 10 Eritreans and a Sudanese man – have applied successfully. The rest are deemed economic migrants and blamed for the crime rates in poorer Tel Aviv neighbourhoods.

Sudanese asylum seeker Anwar Suliman, 38, submitted his application more than four years ago.

“Until today, I didn’t get a yes or no,” he said. “It’s important for us to know the answer – it could change our lives.”

Speaking to Daily Maverick, Suliman detailed a frustrating life lived in the limbo of detention centres and visa application queues.

Back in Sudan, before he fled, he was an archaeologist, specialising in Egyptian and Sudanese history. His political activism twice landed him in jail.

“I had to escape. If I continued, I could get arrested even more. Maybe killed.”

Fifteen years later, Suliman now works in a restaurant in Tel Aviv. Altogether, he’s spent about two years in Israeli detention. It’s not a life, he says.

“But what can we do? Every year some new policy is coming...”

Still, given the choice between returning to Africa or a life behind bars, he would pick the latter.

“I miss Africa, but I’m not ready to go back,” he said. “Rwanda and Uganda are not my homeland.

“I don’t know what comes next. After what happened to us, you don’t have a plan any more. For some people life is clear. But for me nothing is clear.”

***

“It’s a racially motivated system,” Eritrean asylum seeker and community organiser Teklit Michael, 29, said.

After 10 years in Israel, he doesn’t mince his words. There were the people who supported the asylum seekers, “people who know about human dignity and human rights”. But they were in the minority, he said.

“Even the people who are issuing you visas, they treat you like shit, like a slave. They don’t give a shit. They don’t think that you’re a human being like them, that you can suffer, feel pain.”

In November 2017, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke glowingly of Africa on a visit to Kenya.

“We believe in the future of Africa, we love Africa and I would like very much not only to co-operate on an individual basis with each of your countries but also with the African Union,” he said.

But just three months earlier, he promised to return the Tel Aviv neighbourhoods where many Africans live “to the citizens of Israel”. Asylum seekers like Michael were “not refugees”, Netanyahu said, “but infiltrators looking for work”.

“They treat us like animals and blame us for everything,” Michael told Daily Maverick. “They never loved us. They never will love us.”

So why stay in a place that didn’t want him?

“I don’t have a choice. I don’t have a passport. I don’t have anything. I can’t go anywhere. And even if they give me the chance, I don’t know anything about Rwanda.”

Friends who had taken the deal were trafficked out of that country.

“Nobody actually stayed in Rwanda. Their documents are taken on arrival. They tell them to pay money for the hotel and money for the smugglers. Then they take them to the border.

“I don’t have any guarantee for my asylum claim, or for my protection. This is simply human trafficking.

“It’s better for me to stay here in prison than to go to Rwanda or Uganda.”

***

Muhtar did find his way to Uganda eventually – after a brother helped bribe him out of a Sudanese prison.

At 29, he’s now a third-year law student and president of his university’s law society.

“It’s an incredible feeling to finally be following my dreams,” he told Daily Maverick.

He misses Israel. He misses his friends there. But he plans on using his degree to sue the government for what it did to him.

“They lied to me. They took me to a place I didn’t want to go, a place that could have ended my life... If you don’t take risks in life, you will never succeed. But if I knew they were were going to send me to Sudan, I would never have taken that risk. Never.” DM

Photo: African asylum seekers and Israelis residents of South Tel Aviv neighborhoods hold signs in Hebrew that read 'South Tel Aviv is against the deportation' during a protest against the African migrants deportations in southern Tel Aviv, Israel, 09 January 2018. Some 38,000 African asylum seekers live in Israel. EPA-EFE/ABIR SULTAN

- KRISTEN VAN SCHIE

- Africa

Labels:

Africans,

asylum seekers,

Daily Maverick,

Israel,

Kristen Van Schie

19 January 2018

GENOCIDE BY iSRAELIS OF PALESTINIANS

January 18, 2018

In Words and Deeds: The Genesis of Israeli Violence

by Ramzy Baroud

Not a day passes without a prominent Israeli politician or

intellectual making an outrageous statement against Palestinians. Many

of these statements tend to garner little attention or evoke rightly

deserved outrage.

Just recently, Israel’s Minister of Agriculture, Uri Ariel, called for more death and injuries on Palestinians in Gaza.

“What is this special weapon we have that we fire and see pillars of smoke and fire, but nobody gets hurt? It is time for there to be injuries and deaths as well,” he said.

Ariel’s calling for the killing of more Palestinians came on the heels of other repugnant statements concerning a 16-year-old teenager girl, Ahed Tamimi. Ahed was arrested in a violent Israeli army raid at her home in the West Bank village of Nabi Saleh.

A video recording showed her slapping an Israeli soldier a day after the Israeli army shot her cousin in the head, placing him in a coma.

Israeli Education Minister, Naftali Bennett, known for his extremist political views, demanded that Ahed and other Palestinian girls should “spend the rest of their days in prison”.

A prominent Israeli journalist, Ben Caspit, sought yet more punishment. He suggested that Ahed and girls like her should be raped in jail.

“In the case of the girls, we should exact a price at some other opportunity, in the dark, without witnesses and cameras”, he wrote in Hebrew.

This violent and revolting mindset, however, is not new. It is an extension of an old, entrenched belief system that is predicated on a long history of violence.