Kendall Lovett was born on 6 October 1922 in Hobart, Tasmania and when he was about 7 years old and the world was in the middle of a terrible depression and his father, an electrician, was out of a job, and moved his family to Sydney, where Ken grew up.

He went to school in North Bondi and was bullied at school - and outside school. When he was about 12, he started high school at Sydney boys' high school, but didn't get very far before he ws struck by rheumatic fever and was in hospital for a few months, then had a relapse and didn't go back to school - in a formal sense.

In the early years of his adolescence, he discovered early on that he was attracted to males, not females, and subsequently lived his life as a gay man.

Homosexuality was illegal at that stage and remaimed so until gay people started fighting for their rights and gay liberation was formed and the fight was on.

In the USA, apart from small movements amongst gays and lesbians, liberation was not forthcoming until an explosion occurred when the police in New York raided a bar in New York called the Stonewall in 1969 and the fight was on for gay liberation.

As movements around the world grew, and gay voices were being heard everywhere, gay hatred grew as well, aided and abetted by religions which became louder and louder over time and gay people were assaulted - and worse - everywhere, leading to murders in increasing numbers, often aided by those in the community who were hired by government organisations to "keep the peace" - mainly the police.

Ken was a very quietly spoken and mild-mannered person but he discovered early on in his adult years that gays were not tolerated in society and, like many around him in the society in which he lived - he kept his sexual orientation well and truly in the closet.

On the other hand, he discovered the "closet" world and lived his life accordingly. He found gay men in Sydney, and in his late 20s, he and another young man who he was meeting in Sydney and one night the two of them were sitting and talking at the top of the Botanic Gardens in Sydney when some policemen started asking them questions and they had a narrow escape from being arrested.

I learnt bits and pieces of his early life beacuse I only met him when we were both in our 60s but over the years I amanged to fill in bits and pieces of his life as he became involved in many ways with gay politics. and homophobia which was,and still is, so prevalent in our societies.

Ken ran aways with the young man he had been with in Macquarie Street at the beginning of the 1950s and came to Melbourne, where he lived for almost the next 10 years. The young man came home to their residence one night and found Ken in bed with soemone, and that was the end of that relationship, but it didn't take long for Ken to get involved with another man, and when the other man got transferred to London at the beginning of the 1960s, Ken went to London to be with him and they lived together until the other man, also Ken, was transferred back to Australia, to Canberra because that Ken - Skinner - worked for the Australian government and had to go where he was posted. Ken Lovett did not want to go and live in Canberra, so in 1964 when Ken Skinner left Lodnon, Ken Lovett remained until the late 1960s, when his father asked him to return to Sydney and in 1968 he left London for Sydney.

When he returned to Sydney, he stayed with his parents in Willoughby till 1970 when he managed to rent a house in Woolloomooloo and lived there until 1994 when he retired from Choice - Australian Conaumer Association - at th age of 70 and bought a small house in Maryville, Newcastle and stayed there until we bought a house in Preston, Melbourne in 2000 and where we were when Ken died of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in October 2020, leaving me alone and bereft.

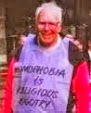

From 1970 until his death in 2020 Ken was an activist to the end, covering as many issues as possible considering his work and family and other activities, encompassing human rights and their abuses.

Living in Woolloomooloo in the heart of the gay world, homophobia and assault did not escape him, and a few times he was lucky to escape injury, after suffering a few burglaries and chases down Crown Street where he lived to escape from the bullies chasing him.

I met Ken in 1988, the year I started coming out as a gay man and I was already getting involved in socialist activist groups by 1988 and after attending a demonstration and ending up in the Domain in Sydney, some young people holding a banner which they were folding, they handed me a leaflet about a demo being held outside the building where the UK consulate was housed. Margaret Thatcher was introducing a homophobic bill called clause 28 to the British parliament making vrious homosexual activities in schools illegal and there were several other anti-gsy items in the bill which contained many human rights aouses.