| How I got my first SMH byline as an act of homophobic intimidation |

| CHIPS

MACKINOLTY Freelance writer |

As

is well known, there are a few

apologies

floating around over the events, and aftermath, of the

June 24, 1978

Gay Mardi Gras in Sydney. First The

Sydney Morning Herald, then

the Legislative Assembly of the NSW Parliament. An

apology from the

police force, we are told, will be a “whole of

government”

decision. I won’t hold my breath.

But

I did get my first naming in the SMH

in

the aftermath of the Mardi Gras violence. My first

byline, as it

were.

There

is a weird disjuncture here. The SMH

apology suggests that publishing the names, addresses

and occupations

of those arrested in the '78 Mardi Gras was, at the

time, some

sort of “standard procedure”. But that is utter

nonsense.

It

was simply never the case that the SMH

published,

as

a matter of "standard procedure", the names of the

hundreds of people a week arrested in Sydney in those

days. It’s

complete bullshit.

In

the last half of the 1970s I was arrested on a number of

occasions

over political actions.

Other

than June 24, 1978, my name was never

reported. Indeed, the SMH

(let alone the police) would have looked like proper

dills on the

occasion that I was arrested, under my own name, with 12

women who

gave their names as Emma Goldman. The SMH

certainly didn’t report this. The ghost of Emma Goldman

would have

smiled.

The

simple truth is that the publication of names, addresses

and

occupations at the time was a calculated effort by the

police, aided

and abetted by the SMH.

Each party was aware, at the time, of the effect it

would produce on

those named. Those effects have been attested to in the

last few days

by ’78ers, and include the suicide of some of those

named in the

SMH.

An apology from the SMH,

let alone the NSW police, should reflect the

catastrophic effects of

their actions.

Some

13 years later I became a stringer for Fairfax papers,

where I worked

for a decade, and have filed occasionally since then. I

got hundreds

of bylines subsequent to first being named in the SMH

in June 1978. I am proud of the work that I did for

papers such as

the SMH

and The

Age.

I was working with some of the best journalists of the

day, and the

SMH's

current editor-in-chief was one of them.

As

such, I have no animus towards Fairfax -- far from it. I

worked with

the best. But

the current “apology” from the SMH

doesn’t go far enough; there is a back story that

should be

acknowledged and, perhaps, explored

Apology to Mardi Gras 1978 Participants (Proof)

Printing

Tips | Print

selected text | Full

Day Hansard Transcript | «

Prior Item |

Item 7 of 80 | Next

Item »

About this Item

|

|

Speakers

|

|

Business

|

Business of the House

|

APOLOGY

TO MARDI GRAS 1978 PARTICIPANTS

Page:

2

Mr BRUCE NOTLEY-SMITH (Coogee) [10.16 a.m.]: I move:

That

this House:

(1) Notes the first Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras took place on 24 June 1978 when over 500 people assembled at Taylor Square for a public demonstration and march to call for an end of the criminalisation of homosexual acts, to discrimination against homosexuals and for a public celebration of love and diversity.

(2) Notes the march proceeded down Oxford Street to Hyde Park and then along William Street towards Kings Cross and that as the parade proceeded, patrons from nearby venues joined in and participants rose to over 2,000.

(3) Notes Police forcibly broke up a peaceful demonstration, making over 50 arrests.

(4) Notes the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age published the names, occupations and addresses of those at arrested, indifferent to the likelihood that those named would subsequently become victims of discrimination and harassment.

(5) Commends the tireless advocacy of the 78ers and their supporters as the upsurge of activism following the first Mardi Gras led to the 1979 repeal of the Summary Offence Act, decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1984 and contributed to an effective community response to the HIV epidemic.

(6) Acknowledges that the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras has as its foundation the violence and struggles of 24 June, subsequent and related protests in 1978 and that Mardi Gras now attracts worldwide attention as a beacon of positive social change.

(7) Commends the work done by the 78ers for their advocacy around ensuring discrimination of this kind is not repeated, as well as raising awareness of the events of 1978.

(8) Affirms an ongoing commitment to an inclusive society and full respect for the rights of all LGBTIQ citizens protected in law.

(9) Places on record an apology to each and every one of the 78ers from the Legislative Assembly for the harm and distress the events of 1978 have had on them and their families and for past discrimination and persecution of the LGBTIQ community.

(1) Notes the first Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras took place on 24 June 1978 when over 500 people assembled at Taylor Square for a public demonstration and march to call for an end of the criminalisation of homosexual acts, to discrimination against homosexuals and for a public celebration of love and diversity.

(2) Notes the march proceeded down Oxford Street to Hyde Park and then along William Street towards Kings Cross and that as the parade proceeded, patrons from nearby venues joined in and participants rose to over 2,000.

(3) Notes Police forcibly broke up a peaceful demonstration, making over 50 arrests.

(4) Notes the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age published the names, occupations and addresses of those at arrested, indifferent to the likelihood that those named would subsequently become victims of discrimination and harassment.

(5) Commends the tireless advocacy of the 78ers and their supporters as the upsurge of activism following the first Mardi Gras led to the 1979 repeal of the Summary Offence Act, decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1984 and contributed to an effective community response to the HIV epidemic.

(6) Acknowledges that the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras has as its foundation the violence and struggles of 24 June, subsequent and related protests in 1978 and that Mardi Gras now attracts worldwide attention as a beacon of positive social change.

(7) Commends the work done by the 78ers for their advocacy around ensuring discrimination of this kind is not repeated, as well as raising awareness of the events of 1978.

(8) Affirms an ongoing commitment to an inclusive society and full respect for the rights of all LGBTIQ citizens protected in law.

(9) Places on record an apology to each and every one of the 78ers from the Legislative Assembly for the harm and distress the events of 1978 have had on them and their families and for past discrimination and persecution of the LGBTIQ community.

There are doubtless many people across the State today who are feel a sense of anticipation that an event they have long hoped for is finally coming—that a parliament of the people has set aside some of its time to deal with a motion such as the one before us. Equally without doubt, there will be many who believe that I am wasting this Parliament's time. Everybody has a right to their opinion and the best opinions are well-informed ones. Few people know the origins of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras and fewer still know what it was like to be gay or lesbian in the 1970s.

Try for a short time to imagine you are a young teenager, a member of a happy, loving—successful even—large family. Your parents shower you with unconditional love, as do your grandparents, aunts and uncles. Your home is always full of people—your brothers, their friends, your friends, your relatives and your neighbours. Your parents' highest priority is your health and happiness and that you will find success in whatever you choose to do—that you will stumble along the way but that they will be there to assist. From those failures you will learn humility and come to understand the value of hard work and persistence, combined with good manners, respect and empathy for others. A good life awaits you.

Imagine that as that young teenager you had a sense that there was something about you. Was it a feeling? Was it an urge? It is something you just cannot quite put your finger on or nail and it has been growing and growing relentlessly for a few years now. It threatened who you thought you were and what was your place in the world. Most disturbingly, it appeared somewhat similar to that affliction suffered by those sick criminals spoken of on radio, seen on television, written about in newspapers, joked about and pitied by all in your world—the homosexual. As a teenager the term "homosexual" sounded so sinister and sick. If it were true, if it was what those feelings actually amounted to, there would be no place for you in the world you comfortably inhabited. You would be expelled from your family, detested by your friends, a criminal to the justice system and a sinner to the church. Life would be over.

On 24 June 1978 those are the feelings that were running through my 14-year-old head. How can I be so sure? Because those were the thoughts that filled my brain all that year, years before and years beyond. That night of 24 June would also have been my youngest brother Anthony's tenth birthday had he not been hit by a car and killed three years earlier. Anthony's death had shaken our family to the core, and made us closer and stronger. So that night the cloak of melancholy weighed even more heavily on my teenage shoulders. So as I drifted off to sleep that evening, eager for sleep to relieve me from this daily torment, across town there was assembling a group of people—many of them those sick and perverse people that I saw regularly on the telly. They were about to set in motion a series of events that would change the course of history and change the way vulnerable 14-year-old boys and girls would value their worth and their prospects in life in the years ahead. I am told by those that assembled in Taylor Square on that cold night that the atmosphere was electric—a march down Oxford Street calling for the end to the criminalisation of homosexual acts, demanding equality before the law and respect from the community. [Extension of time agreed to.]

But this march was to be different. Ron Austin suggested at a meeting where the march was being planned that participants should dress up in colourful fancy dress—the more outrageous the better. The meeting agreed and a name was suggested. This was not to be any old protest march—this was to be the Gay Mardi Gras. The march set off down Oxford Street and continued into College Street gathering hundreds, maybe thousands, along the way. One of the chants was: "Out of the bars and into the streets", as supporters left their drinks behind in the many venues along the way and joined in the parade. The march took on a momentum of its own and now, too big to disperse, it headed up William Street to Kings Cross. There, hemmed in by the police, the parade turned into a riot. Fifty-three arrests were made and many participants assaulted. It was such a disappointing end to something that started out so joyously.

In the days, weeks and months to come, as those arrested appeared in court, their names published in the Fairfax media, many were ostracised from their family, dumped by their friends and sacked by their employers, not for being arrested but because they were homosexual. For the mistreatment you suffered that evening, as a member of this Parliament who oversaw the events of that night, I apologise and I say sorry. As a member of the Parliament which dragged its feet in the decriminalisation of homosexual acts, I apologise and say sorry. And as a proud gay man and member of Parliament offering this apology I say thank you. The actions you took on 24 June 1978 have been vindicated. The pain and suffering meted out to you on that night and afterwards was undeserved. On that evening you lit a flame of the gay rights movement in Sydney that burned its way to law reform and societal acceptance. To the 78ers I say sorry but also thank you.Members stood in acclamation.Mr JOHN ROBERTSON (Blacktown) [10.27 a.m.]: I speak with pride in supporting this motion. I do so because today is a significant event for so many. It is important that we acknowledge what happened almost 38 years ago—in fact, three months from now it will be 38 years ago. It is important for a number of reasons, not least of which is what happened on that evening of 24 June 1978. It is important because we should talk about it, particularly for young people. For young people there is almost an acceptance of the rights that exist for people in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and questioning [LGBTIQ] community. But those rights, like so many, are hard fought for, and were hard fought for by the 78ers. They were hard fought for on that night that ended in what can only be described as the vicious bashing of so many people who merely sought to stake their claim for equality and to be treated just like everybody else in our society.

Those people stood up at a time when people were bashed because they were suspected of being homosexuals; at a time when it was a legal defence to say, "I was suffering from gay panic"; and at a time when homosexuality was a crime in this State. Those people demonstrated courage and conviction as they stood up and said, "We are people just like everyone else. We love like everybody else and we deserve to be treated just like everyone else." It was at a different time, but that in no way accepts the treatment that was meted out to people at that time or before. As the Parliament apologises to the 78ers, I read in the Sydney Morning Herald this morning that it also has apologised. I am not sure how others felt but I felt a slight disappointment with that apology. As I read it, I felt there was some qualification in it, that that was how the media at the time reported those events. To me, the apology did not feel like it was unqualified. I am proud that this Parliament is giving an unqualified, unreserved apology to the 78ers.

We recognise that change is achieved only through activism and having the courage to stand up. We should be thankful because the 78ers have achieved something significant. I now mention the significant changes that have occurred. The Summary Offences Act was repealed, which was the justification in 1978 for the arrest of the 78ers; the New South Wales Labor Council threw its support behind homosexual law reform in 1980; in 1984 this Parliament decriminalised homosexuality; it recognised same-sex relationships; the Property (Relationships) Legislation Amendment Bill was introduced, which recognised same-sex couples in a whole range of legislation; workers compensation laws were changed; this Parliament made changes to recognise mothers as legal parents of children born through donor insemination; in 2010 the Attorney General announced that the State Government would introduce legislation for a statewide relationships register and introduced a bill that was approved in this Chamber by a vote of 62:9 on 11 May 2010; same-sex adoption was legalised in September 2010, and I was proud to participate in that debate in the other place; and the Federal Parliament removed discriminatory laws against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex [LGBTI] community. [Extension of time agreed to.]

Amendments have been made to 85 laws in the Commonwealth Parliament that have changed the way the LGBTI community is treated, whether it is tax, superannuation, social security, family assistance, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, the Medicare levy or aged care. Changes have been made to child support laws, immigration, citizenship laws, veterans affairs laws, employment law and family law. All that was achieved because of the activism of the 78ers who set in train a program for reform to see progress made so that members of the LGBTI community could feel they were genuinely part of our community. While apologising today, I also want to thank the 78ers. I do so as the parent of a son who has had the benefit and the privilege of going to school and feeling free to be who he really is, not having to feel like he has to hide who he is. He was supported by his teachers and fellow students who acknowledged him. They embraced him and are friends with him today, despite what he is.

While much has been achieved, there is much more to do. It is important to talk about this today so that we motivate young people, not only those from the LGBTI community but also young people across our State and nation. Right now there are two things that are disturbing. First, the Safe Schools program is now under some form of investigation by the Federal Parliament. It is sad because the program is about stamping out bullying and breaking down ignorance so everyone can feel that they are a part of our community. It is a program to stop the bigotry that we still witness. My son says there are still parts of Sydney that he does not feel safe walking around. The Safe Schools program is important because it is about making people understand that their ignorance or some jibe yelled out from across the street or down the road makes people feel unsafe and no-one should feel unsafe. Our schools are the right place to implement the anti-bullying programs. We should be proud to support the Safe Schools program. We should be encouraging more people to undertake that program so that we no longer have the ignorance and bigotry that led to the behaviour we saw in 1978.

The second disturbing thing relates to that old chestnut—same-sex marriage. I want my son to enjoy same-sex marriage, if he so chooses. I want everyone, regardless of who they are, to be able to enjoy the benefits that we all enjoy, if they so choose. It will happen, but it will happen only when we talk about what the 78ers did and what achievements they made. We must continue our campaign and our activism on the ground to dispel any ignorance. Ignorance is what has led us to this debate. Marriage is a construct that did not exist in our churches and religious systems until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Prior to that, marriage was a civil ceremony that some people chose to have blessed in a church. It was not until the latter part of the sixteenth century that the churches decided they would get on board and sanctify marriage. It is a human construct and not many people know that. Therefore, people's ignorance of that fact has led us to this debate.

We will continue to campaign on same-sex marriage because it is a great and outstanding injustice for the LGBTI community. The sky will not fall in. Our society will not change for the worst; our society will change for the better. I can say that confidently because in 1978 the same arguments were being advanced: "These people are not normal; if we recognise this, it will all end." Almost 38 years later we have seen where it ends. We have a society that is more inclusive and we enjoy much from some in our community who contribute more than others. We should be prepared to stand up and say that everyone deserves the right to get married, if they choose, but we should not sit in this place and say, "We will decide how you behave and whether you publicly state your love for someone else and have it recognised and acknowledged in a ceremony." On behalf of the Opposition the member for Coogee and I apologise to the 78ers. More importantly, I say thank you. Thank you for standing up for what was right and has proven to be right. To all the young people in the gallery I say, "Stand up and keep fighting. Stand up and continue your activism, because right will always win out."TEMPORARY SPEAKER (Ms Melanie Gibbons): Order! I inform people in the gallery that it is common practice in the New South Wales Parliament that no videos or photographs be taken of parliamentary proceedings. Today we will turn a blind eye and allow photographs to be taken. However, videotaping the proceedings is not permitted.

Mr ALEX GREENWICH (Sydney) [10.38 a.m.]: I acknowledge the leaders, elders and allies of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex [LGBTI] community in the gallery today and those watching this on the web stream at home. I also acknowledge the leadership of the member for Coogee for moving this motion; the Government for prioritising this motion today before the Mardi Gras festival and parade begins; and the cross-party working group, which includes members from The Nationals, the Liberal Party, the Labor Party, The Greens and Independents who have worked together to make this motion happen. Indeed, our Federal politicians could learn a lot from us about working together to achieve important reforms.

Many 78ers who participated in that peaceful march, which ended in brutality from government agencies, could not imagine back then a day when we would have two openly gay members of Parliament sitting on either side of this Chamber and delivering a formal apology on behalf of this Parliament for what happened to them. Indeed, we are doing that in the oldest, longest-running Parliament in the Commonwealth. The New South Wales Parliament is also the gayest parliament in Australia. It has more gay and lesbian members than any Australian Parliament, with members from the lower House and upper House all listening to the debate today, which is wonderful. We are all here because of the 78ers—because of their bravery, courage and sacrifice. They continue to inspire us to advocate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex [LGBTI] communities and to work towards fairer and more equal laws. Just like the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade, our work has at its foundation the pain and struggles of the 78ers. The 78ers have used the positivity of the rally, in which thousands participated, and the trauma that followed to advance fairness and acceptance.

In 1978, being gay had social and economic risks. Parents disowned their gay and lesbian kids, and employers fired LGBTI people. Gay homosexual sex was illegal. There were significant and devastating repercussions for the 53 people who were arrested that night and who had their names, addresses and occupations published in the Sydney Morning Herald. People lost their jobs and their families. Barbarella Karpinski, who I believe is here today, was only a teenager when she was arrested, and her outing meant that she could no longer see her nieces, nephews and other family members. Her parents were also maligned for supporting her. [Extension of time agreed to.]

The 78ers report that police targeted women and the most vulnerable. Sandi Banks, who I understand is also here today, described heavy bruising across her chest and arms that lasted for weeks. Laurie Steele, one 78er who was arrested, left Australia soon after charges were dropped in court and did not return until 2006. Many others suffered, and I hope that this apology will encourage more people to tell their stories. I am very sorry that some of the 78ers are not around to hear this apology today. I am proud to represent the inner city areas of Darlinghurst, Surry Hills and Kings Cross, which were—and still are—the heart of the LGBTI communities and welcomed gay men and lesbians. But that was not enough to protect them when discrimination was rife and lawful. The brutality that took place on that evening in 1978 on members of the LGBTI community shows what can happen when a society and the law treat a group of people as inferior and, as a result, provide fewer protections. Where the law is not equal, people will always be at risk of being treated as lesser citizens and things can get out of hand, as they did in 1978.

It was not just in 1978 that police turned on peaceful demonstrators; there was a long history of homophobia and violence during the 1980s and 1990s in Sydney. This included gay bashings, hate crimes and murders, with police involved in entrapment, abuse, victimisation and cover-ups. I welcome the work of Superintendent Tony Crandell of Surry Hills Local Area Command for advancing police relations with LGBTI communities. He and police in other inner city commands are building trust by working with LGBTI communities. But that has not always been the case, and that is why we are here today. My good friend Lance Day—another 78er who is in the gallery today—tells me he had a gay friend who was a police officer there that night. The whole thing was too much for him and he applied for a transfer as he was petrified that the force would find out he was gay and would have him sacked.

The struggle of the 78ers has helped achieve so much but I know that those who suffered want this apology to be more than a ceremonial sorry; they want this apology to be a turning point that leads to full equality by the law. I commit to those 78ers and to the LGBTI community that I am dedicated to achieving reforms, including removal of discrimination against LGBTI people, to transgender and intersex reforms, and to marriage equality. I support the motion. As the member for Sydney who represents the area in which this brutality occurred on that night in 1978, I extend my apology to the 78ers and my thanks to them for their sacrifice and courage that continues to inspire me and others to achieve reforms in this place. I thank the 78ers for using that experience to make this State fairer and more accepting of LGBTI people. Again, I am sorry and I thank them.Mr GARETH WARD (Kiama—Parliamentary Secretary) [10.45 a.m.]: The fight for social change and social justice has often made the most ordinary people become heroes. They were ordinary people until a moment in time changed them; emotions moved them to be more than simply ordinary. William Wilberforce, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Rosa Parks and Charles Perkins all either confronted or experienced injustice and pain. It was these experiences combined with fortitude and character that gave them the tools to be much more than simply ordinary people; it gave them the courage to stand up in order to make the world a more tolerant and accepting place.

On 24 June 24 1978, more than 500 activists took to Taylor Square in Darlinghurst in support and celebration of New York's Stonewall movement and to call for an end to criminalisation of homosexual acts and discrimination against homosexuals. The peaceful movement ended in violence and public shaming at the hands of the police, government and media. When the marchers moved from Taylor Square to Hyde Park, the police confiscated their truck and sound system in spite of a permit being issued for the rally. The crowd began to move towards Kings Cross. Once there, the police swooped in, blocking the dispersing crowd and throwing people into paddy wagons. The crowd fought back and 53 were subsequently charged at Darlinghurst police station. In the words of Ken Davis:

You

could hear them in Darlinghurst police station being beaten

up and

crying out from pain. The night had gone from nerve-wracking

to

exhilarating to traumatic all in the space of a few hours.

The police

attack made us more determined to run Mardi Gras the next

year.

Although most charges were eventually dropped, the Sydney Morning Herald shamefully published the names, occupations and addresses of those arrested in full, outing many and causing some to lose their jobs. Protests and arrests continued throughout 1978. On 15 July more than 2,000 gay men, lesbians and supporters took part in the largest gay rights rally that had been held. The police responded by arresting 14 activists. On 27 August gay men and lesbians tried to join up with a Right to Life rally after attending the fourth National Homosexual Conference and 104 people were arrested. In all, 178 were arrested in the Mardi Gras and subsequent protests. The protracted court cases for the arrestees and ongoing protests served to engage a huge number of additional people in the cause of gay rights—galvanising the movement for gay law reform and the right for the community to protest in the streets.

Having been born with a disability, I know what it is like to feel discrimination—to be treated in a manner that falls far short of what anyone would consider acceptable. These experiences remind me that whilst law reform is essential, attitudes must also change. History tells us that so often change is slow and painful, but it does not make the cause any less important. Representing a regional electorate, I know that many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer people [LGBTIQ], and particularly young people, still feel isolated, afraid and alone. Tragically, sexual orientation is still a cause for youth suicide, sometimes prompted by the intolerance and callousness of peers and even family. I am sure those gathering in support of equality on 24 June 1978 had no clue about what was to follow on that chilly winter evening, but they should feel proud that their brave actions led to a freer and more confident society. [Extension of time agreed to.]

Like those who had pioneered social change and progress before them, their actions led to this Parliament acting after many years of discrimination and even vilification. In my inaugural speech in this place I described myself as a classic liberal. I believe in the rights of individuals; I believe in personal liberties and choice; I believe that every person is best placed to make decisions about their life; and today I believe this Parliament owes a deep, sincere and unreserved apology for the treatment of people who could see the light would shine in the darkness and the darkness had not overcome it.

NSW Parliament apologises toMardi Gras '78ers

Thu 25th Feb, 2016 in Local News

New South Wales’ Parliament has today apologised to each and every 1978 Sydney Mardi Gras protester for the ill treatment they suffered almost 38 years ago.

The

apology, which was brought forward by out gay Liberal

member of

Coogee Bruce

Notley-Smith,

had cross-party support and moved through both houses of

NSW

legislature without disapproval by any MP.

All

MPs present, including Premier Mike

Baird and

everyone in the packed public gallery, rose to their

feet with cheers

and applause after the apology was read out. There were

tears from

some of the ‘78ers present, who had waited a long time

for the

state to express its regret at what had happened to them

all those

years ago.

“The first Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras took place on 24 June 1978 when over 500 people assembled at Taylor Square for a public demonstration and march to call for an end of the criminalisation of homosexual acts, to discrimination against homosexuals and for a public celebration of love and diversity,” the apology began.

“The

march proceeded down Oxford Street to Hyde Park and then

along

William Street towards Kings Cross – as the parade

proceeded,

patrons from nearby venues joined in and participants rose

to over

2,000. Police forcibly broke up a peaceful demonstration,

making over

50 arrests.

”[NSW’s

Parliament] places on record an apology to each and every

one of the

‘78ers from the Legislative Assembly for the harm and

distress the

events of 1978 have had on them and their families and for

the past

discrimination and persecution of the LGBTIQ community.”

The

‘78ers were also officially commended by NSW Parliament for

their

advocacy around ensuring discrimination of this kind is not

repeated.

In

June 1978 the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age

newspapers published

the names, occupations and addresses of those who were

arrested. The

Herald’s now-editor Darren

Goodsir apologised

on behalf of the newspaper yesterday.

Several

MPs and ‘78ers mentioned today that a formal apology by

NSW Police

for their brutality in dealing with the protestors is

also necessary.

In particular, the Greens’ Jenny

Leong put

descriptions of police brutality on the record and noted

“an

apology from the NSW police has not yet been forthcoming

and that is

one part of righting these wrongs that must occur.

“This

is a living apology. It’s the start of a commitment to

ensure our

laws continue progressing to treat LGBTI people fairly,” she

said.

“In making this apology in Parliament today, we need to

ensure

these kinds of events never again repeat, by making sure our

laws are

equal.”

Out

gay Sydney MP Alex

Greenwich said

he was grateful to the ‘78ers for helping to bring about

the

changes in society needed for us now to have “the gayest

Parliament

in Australia.”

“We

have more gay and lesbian members than any parliament in

Australia

has ever had,” he said proudly. “And we are all here

because

of your bravery.

You used the positivity of the march and the trauma that

followed to

advance the rights of gay and lesbian people around

Australia.”

After

the apology, Labor MP John

Robertson rose

to mention that he’s proud that his gay son is embraced

and

welcomed at his school.

“Our

schools are the place for programs like Safe Schools which

breaks

down ignorance and bigotry which we had in 1978,” he noted.

“So

I rise to apologise, and I rise to say thank you. To the

young people

here, stand up and continue your activism. Right will always

win

out.”

NSW Government apologises for ill treatment of protesters at Sydney’s first Mardi Gras in 1978

FEBRUARY

26, 201610:48AM

Police violently arresting participants during the Mardi Gras, Day of International Gay Solidarity, June 24 1978. Picture: Ross Macarthur or John Cousins for Campaign magazine / Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Benedict

Brooknews.com.au

WHEN

Steve Warren went bounding out of the pub to join a

street party in

the heart of Sydney the only thing on his mind was

being part of an

impromptu celebration.

Yet

by the end of the night, he would find himself in the centre

of a

full-blown riot, listening powerless as his friends cried

out,

desperate for help.

“It

had been a great night, and then the police stared grabbing

people

and throwing them,” Mr Warren told news.com.au. “People were

screaming … we didn’t know why they were doing it.”

The

events of that night, when police arrested more than 50

people in

Kings Cross, allegedly beating many of them, would change

the face of

Sydney forever.

Today,

almost 40 years later, the NSW Government officially

apologised for

the discrimination they suffered at Sydney’s first Mardi

Gras in

1978.

For

some, it’s too little, too late and means nothing unless the

police

themselves apologise for their actions.

Mr

Warren was just 21 when he became involved in the

demonstration that

would lead to Sydney’s now world-famous gay and lesbian

Mardi Gras

parade, which this year takes over the city’s streets on

Sunday,

March 5.

It

was June 24, 1978 and Mr Warren, who was a budding rock

musician, was

having a drink after a day that had already involved a rally

at

Sydney Town Hall to protest against the continued

criminalisation of

homosexuality in NSW despite, by that time, it being legal

in a

number of other states.

Morning

march for the Day of International Gay Solidarity,

June 24 1978.

Picture: Ross Macarthur or John Cousins for Campaign

magazine /

Australian Lesbian and Gay ArchivesSource:Supplied

‘OUT

OF THE BARS, ONTO THE STREETS’

That

night, a group of revellers decided to amble down Oxford

Street, then

— as it is now — the heart of the city’s gay community.

“They

were yelling ‘out of the bars, onto the streets’ and a drag

queen

called Trixie Le Bon led us all down the stairs and that’s

how we

ended up in the parade,” he said.

“It

was initially really fun with no dramas, but when we got to

Hyde

Park, the police confiscated the only float and dragged my

friend

Lance out of the truck and tried to arrest him.”

The

crowd swiftly decided to head towards Kings Cross, where

another

clutch of gay bars and more people to join the march could

be found.

But

they were walking into a trap. With hindsight, said Mr

Warren, the

signs were there. Police cars had been spotted “flying down”

nearby streets while some people had remarked that the

officers

weren’t wearing their badges displaying their ID numbers.

“That

was usually a bad sign, once the numbers were off people

knew it was

going to turn ugly,” he said.

Before

long, the marchers were surrounded. “The police started

grabbing

people, pulling them into paddy wagons. Throwing them hard

against

the metal walls of the vans and slamming the doors, often on

people’s

hands.

“There

were people lying on the ground, there were steel bins being

thrown

left, right and centre, it was pandemonium. It was violent

and it

really was a riot in the end.

“I

was young and I didn’t understand why the state was reacting

that

way to people,” he said.

“It

was a contradiction, we could walk down Oxford Street, happy

and

skipping, even interacting with police, but if you left

Oxford Street

it was a completely different story.”

Mr

Warren dodged the blows and headed towards the relative

safety of

Oxford Street. On the way he passed Darlinghurst Police

Station where

53 people, arrested during the march, were being held.

“You

could hear screams from the police station, people yelling

and

calling out from inside the cells. There was one person who

was

bashed by the police, his ribs were damaged and he was all

bruised.”

People

outside put enough money into a hat for bail to get most

of the group

out of jail. But the trauma was far from over with the Sydney

Morning Herald subsequently

publishing the details of those arrested, leading many

to suffer

harassment and even lose their jobs.

On

Wednesday, Fairfax Media apologised for the decades-old

coverage.

Openly

gay Liberal MP for Coogee, Bruce Notley-Smith, delivered

today’s

apology in the NSW Parliament. Talking to news.com.au he

said the

hostility gay people once faced shouldn’t be forgotten.

Steve Warren was just 21 and in a rock band when he found himself in the middle of a riot in Sydney’s Kings Cross.Source:Supplied

Steve Warren was just 21 and in a rock band when he found himself in the middle of a riot in Sydney’s Kings Cross.Source:Supplied

Bruce Notley-Smith, pictured with Coco Jumbo and Krystal Kleer, made the official apology in Parliament. Picture: John AppleyardSource:News Corp Australia

“Marching

on the street was an incredibly brave thing to do but no one

would

have expected the parade to end in such violence.

“We

should recognise the profound events of that night in June

1978 had

on the lives of not only those people who were arrested but

also the

major influence it had on the subsequent liberation of

lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people.”

Asked

if it would have been an even greater sign of acceptance if

the NSW

Premier Mike Baird had made the apology, Mr Notley-Smith

said it

wasn’t for him to dictate who should talk in Parliament.

Mardi Gras is now one of the world’s most well-known festivals visited by stars such as Kylie Minogue. Picture: Dan Boud/Destination NSWSource:Supplied

‘APOLOGY

IS TOO LITTLE TOO LATE’

Many

of the cases were later thrown out of court, particularly

when TV

footage came to light which appeared to show police as the

aggressors. A month later people once again marched along

Oxford

Street and, once again, clashed with police.

When

protesters tried to attend a number of the court

appearances, Mr

Warren said “police barricaded the courthouse, it was just

insane

what was going on”.

Mr

Warren, who, along with the others that marched that day are

collectively known as ‘78ers’, acknowledged a number of

LGBTI

people view the apology as hollow.

“For

some the apology is too little too late, for some it’s

lacking

because there is not a direct apology from the police and it

certainly doesn’t take away the hurt we went through. But

it’s a

good first step and it’s important to acknowledge the

struggle.”

In

a statement to news.com.au, a NSW Police spokesman confirmed

the

force would not apologise in their own right.

“At

this time this is a matter for consideration by the whole

Government.

However, NSW Police has developed rewarding relationships

with

members and stakeholders within LGBTI communities,” the

statement

read.

The

force pointed to the more than 200 officers that have

signed to the

Gay and Lesbian Liaison Officer program.

The

protest became an annual rally which is now known as Mardi

Gras.

Officially backed by the NSW Government, and big name

sponsors

including Qantas and ANZ, the festival is estimated to pump

almost

$40 million into the state’s economy.

Steve Warren (second from right) pictured with other 78ers — the people who were at the first Mardi Gras, and Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore (third from left). Picture: supplied.Source:Supplied

‘WE

HAVE ACHIEVED PLENTY’

Homosexuality

was legalised in NSW by the Wran Government in 1984.

Tasmania would

become the last state to do so as recently as 1997.

There

were still battles to be fought, Mr Warren said, pointing to

a recent

spate of gay bashings in Sydney, the opposition to the

LGBTI-focused

Safe Schools program, and the upcoming plebiscite on

marriage

equality, “which the government doesn’t even have to act

upon”.

“As

Mardi Gras approaches, we do think back and they’re not good

memories but when you start going up Oxford Street it really

hits you

what we’ve achieved,” he said.

“It’s

ironic that we had to go through such an awful struggle to

lead us

somewhere that is really positive.”

featured

video

Play

0:00

/

45:08

Fullscreen

Mute

Late in Life Lesbians

Three

women, three wives, three mothers, they were each living out

the

American dream, until they realized they were living a lie.

How some

womenhave to keep their secret for fear of breaking their

family

apart.

CALLS MOUNT FOR NSW POLICE TO APOLOGISE TO 78ERS

FEB25

LAST

UPDATED

// THURSDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 2016 15:47WRITTEN BY // Cec

Busby

The

pressure is mounting for NSW Police to issue an apology to

the 78ers

– the first participants of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi

Gras –

following an historic apology by members of the NSW

Legislative

Assembly this morning.

The

parliamentary apology follows an apology by Fairfax media

for

publishing the names and addresses of the 53 people arrested

at the

protest march on June 24 1978.

Greens

member for Newtown Jenny Leong described the parliamentary

apology as

significant but said there was more to come.

“I

think it’s clear what we’ve seen today is an amazing step

forward

– but there is one party remaining that hasn’t apologised –

that is the NSW police," Leong said.

“I

think it was pretty clear from the response in the chamber

today that

everyone recognises that that is an apology that is

outstanding and

I commit to that. We need to recognise that the wrongs of

the past

need to be acknowledged and that includes wrongs

acknowledged by all

those who are perpetrators of the violence." said Leong at

a

press conference following the histioric apology.

“The

obvious and necessary step is for an apology to be issued by

the NSW

police. Until this is done, all the positive work being

undertaken

through LGBTIQ liaison officers and community outreach at

events like

Mardi Gras and Wear it Purple Day will not be able to

achieve their

full potential.

“I

am calling on the NSW Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione to

recognise the violence and intimidation perpetrated by NSW

police on

June 24, 1978 and offer a formal apology to all 78ers for

the hurt

and suffering caused by the actions of NSW police,” she

said.

PHOTOS

Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Government apologises to first generation of protesters

25.2.2016

PHOTO: 53 people were arrested during the first 1978 protest which grew into the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras.(Photo: Fairfax media)

The

New South Wales Government has offered an apology to

participants in

Sydney's first ever Mardi Gras, who were arrested and

bashed by

police when attempting to parade in 1978.

After

they were arrested, many of the protesters had their names,

addresses

and professions published in the press.

In

all, 53 people were arrested and many were savagely beaten

by police.

On

Thursday morning, Liberal MP Bruce Notley-Smith delivered

the

Government's apology.

"You

were the game changers."

Liberal

MP Bruce Notley Smith

"We

recognise that you were ill-treated, you were mistreated,

you were

embarrassed and shamed, and it was wrong," he said.

"I

hope it's not too late that you can accept an apology but

also we

want to recognise that for all of that pain that you went

through,

you brought about fundamental change in this society and

fundamental

change for the many gay and lesbian people like myself, who

can be

open and relaxed about ourselves.

"You

were the game changers."

He

continued: "For the mistreatment you suffered that evening,

as a

member of this Parliament, who oversaw the events of that

night, I

apologise, and I say sorry.

"As

a member of a parliament that dragged its feet on the

decriminalisation of homosexual acts I apologise."

The

apology received a long round of applause from the public

gallery,

which was filled with some of the activists who took part in

the

march.

Former

opposition leader John Robertson said it was an important

moment.

"Because

we should talk about it, particularly for young people,"

he told parliament.

"For

young people, there is almost an acceptance of the rights

that

exist for people from the LGBTIQ community."

Mr

Robertson noted that the Sydney Morning Herald also

apologised for its coverage but

he expressed disappointment at its wording.

He

said the Herald's apology did not seem to be unqualified.

'I thought I was going to die'

In

just over a week, Sydney's world famous Gay and Lesbian

Mardi Gras

will once more turn parts of Sydney into a celebration of

diversity.

But

almost four decades ago, things got off to a very different

start.

Peter

Murphy was 25 and still struggles to speak about what

happened the

night after he was thrown into a police van and taken back

to the

Darlinghurst police station.

"I

was singled out and bashed, thoroughly. There were just two

police

present and only one of them beat me," he said.

"He

would have kept going, except the other guy finally said

stop.

"So

I was convulsing at the time he said 'stop'. I thought I was

going to

die."

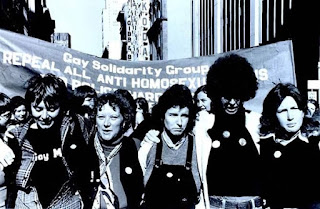

Diane

Minnis was 26 at the time, a part of the gay solidarity

group.

She

described the police as "whaling in" on the that first

group of marchers, who became known as the "78ers".

"They

were huge blokes and they were just grabbing people,

throwing them

bodily into paddy wagons and smashing people.

"It

was carnage."

After

the mass arrests, Ms Minnis joined a large group of people

outside

the Darlinghurst police station.

"We

sang 'We Shall Overcome' and people that were inside said

they could

hear it and it gave them some courage.

"But

what we didn't know is how badly Peter Murphy was bashed in

the cells

at that stage."

Sally

Abrahams from Yamba in northern NSW was in Sydney in 1978.

She

entered several gay nightclubs after the melee broke out and

asked

for the music to be turned off so she could call for help

over the

loud speakers.

"I

was determined not to be arrested, but my girlfriend at the

time, I

watched her being bashed and thrown into the back of a paddy

wagon,"

she said.

"I

announced what was happening at the nightclubs and asked if

there

were any lawyers to come and please help us, because there

were

people being beaten up and harmed, and there were quite a

few people

who came with me.

"It's

worth noting that all of the charges were eventually dropped

against

everybody because we didn't do anything wrong, it was the

police's

behaviour that was terrible."

Writer

David Marr said he went to the court on the Monday morning

following

the arrests, which had been barricaded by police despite

orders from

the magistrate to let the public in.

"It

was a wild day on the Monday as well as on the Saturday

night,"

he told 702 ABC Sydney.

"The

coppers hated the poofs, they hated them. And they hated the

lesbians

perhaps even more than that."

Marr,

who wrote extensively on the events of that weekend, said

the police

used paddy wagons to encircle the last of the marchers

before beating

and arresting them.

"They

grabbed the woman by their breasts, by their hair...they

dragged them

along the road by their hair," he said.

"It

was the first bit of gay journalism I did and I was

terrified even at

that."

Police made reform inescapable: David Marr

Mr

Marr said that reform, including the legalisation of

sexuality,

became inevitable after that weekend.

Sydney

"could not believe the hate that was in the air that night."

"When

the police overstep the mark, they make reform inescapable,"

he

said.

Peter

Murphy said he thought the speech and apology was a good

step, but it

could have gone further.

"The

police are only mentioned once," he said.

"It

is very important that Parliament makes this statement.

"I'm

hoping that this will lead to the police command also making

a

whole-hearted apology for what took place in 1978, so that

we can

move past what's clearly a sort of official intolerance of

homophobic

attitudes in the police force.

"And

we will change that culture."

How the beatings and humiliations of the 1978 Sydney Mardi Gras made reform inescapable

An

overdue apology is to be debated in NSW parliament for

the violence

of that night. But we should thank the police, writes David

Marr,

because their zeal and brutality were so out of kilter

with the

city’s attitudes, they spurred it to action

he

steam had gone out of Mardi Gras by the time the parade

reached the

El Alamein fountain in Kings Cross. For an hour or so a

couple of

thousand gays and lesbians, their friends and civil

libertarians, had

marched throughSydney on

a midwinter night calling for freedom. Now it was time

for a drink.

But

the police had other ideas. As the marchers began to

disperse, they

found their way blocked by a fleet of paddy wagons. Bashings

and

arrests began.

A

riot outside New York’s Stonewall Bar a few years earlier

had

kicked fresh life into gay law reform in America. On this

night in

June 1978, Stonewall was happening all over again in

Sydney’s

Darlinghurst Road.

On

Thursday an

apology is to be debated in the New South Wales

parliament this

week for

the violence of the police that night. About time. But

we should

thank the cops, too, because their zeal and brutality

were so out of

kilter with the city’s take on gay life they made reform

in New

South Wales inescapable.

I

wasn’t on the march – I’m not one of the honoured “78-ers”

– but I was at the court that Monday to find the witnesses I

needed

to do what we did on The National Times in those days: write

a big

narrative of what happened in the hours after a happy crowd

chanting

“Out of the bars and into the streets” set off down Oxford

Street

behind a truck at 10.30 pm.

State MPs to apologise for mistreatment of first Sydney Mardi Gras marchers

Read

more

I’ve

been back to my notes. They are better than the story I

wrote nearly

40 years ago. Names swim out of the past. Aids has claimed

some of

these warriors. A few of the lawyers on the streets that

night are

coming to the end of their time as judges in NSW and federal

courts.

Some of the braver souls on the march have escaped

respectability.

We’re all getting old.

Revellers

poured out of the bars. The police hurried them all down the

road.

Within 20 minutes they had reached Hyde Park where the

police permit

issued for the march decreed the demonstration had to end.

It was too

soon.

The

park filled with people expecting speeches but wishing for a

concert.

The police were having neither. They ordered the truck and

its

loudspeakers to drive away. The driver refused, was dragged

out and

fled into the crowd. The police ripped out the speaker

leads.

As

the first arrests were made the crowd began chanting, “Stop

police

attacks on gays, women and blacks.” It was an old favourite.

Once

the loudspeakers were disabled, the crowd was left to make

up its own

mind – by chanting. A chorus began: “March to the Cross.

March to

the Cross.”

This

was an action with only one purpose: to make arrests

On

William Street happy bravado was restored. The ruckus

round the truck

was forgotten. It was party time again. People left the

footpaths to

join the happy procession. “Ho-ho-homosexual,” chanted

the

marchers. Also a new favourite: “Dare to struggle, dare

to fight,

smash the Festival

of Light.”

Word

somehow swept through the crowd that their destination was

now the El

Alamein fountain. It made sense. The fountain is the

bullseye of the

Cross. But even before they arrived, there was a sense that

the night

was over. Old timers sang mournfully, “We Shall Not be

Moved”.

People broke off to buy ice creams.

But

about midnight the paddy wagons moved into place, their

sirens

blaring. The marchers were packed tight in a stretch of

Darlinghurst

Road with no way of dispersing. This was an action with only

one

purpose: to make arrests. Police removed their badges and

began

grabbing people.

In

the melee of the next half an hour the demonstrators were

joined by

locals, drunks and a couple of bikies. The queers fought

back.

“Police were using fists and boots,” one of the marchers,

Jeff

McCarthy, told me. “Beer cans were being thrown, full ones

from the

back of the footpath, bottles of Spumante, shoes, at least

one

garbage can from each side of the road.”

The stories you need to read, in one handy email

Read

more

There

was screaming and crying. McCarthy saw a policeman kicked in

the

balls. “Someone was thrown half into a van, landed on his

stomach

on the edge of the door, then police slamming the door on

his legs.”

Several

witnesses confirmed that incident and widely shared was

McCarthy’s

impression that the police were particularly targeting

women. “They

seemed to make their attacks especially sexual,” McCarthy

said.

“Women were dragged along by the hair … One woman was

grabbed by

the tits. She called, ‘Let go of my tits’ and was charged

with

offensive language.”

Paddy

wagons ferried the arrested to the nearby Darlinghurst

police station

followed by several hundred marchers who took up a vigil in

the

street. This was the headquarters of the notorious No 3

Division that

policed gay Sydney. There was antagonism of long standing

between

this station and that community. Darlinghurst police frankly

regarded

homosexuals as criminals.

More

demonstrators were arrested. Heads connected with paddy

wagon

mirrors. Three big constables dragged a woman into the

station by the

hair.

Inside,

police refused for hours to bail any of the 50 prisoners.

Peter

Murphy was the first to emerge at about 4am. He had been

bashed in

the cells. Dr Jim Walker told me: “Murphy had bruises of the

head,

ribs, stomach arms and legs. His lower leg was particularly

swollen

to twice its normal size. I suspected a broken fibula.”

Murphy

was taken to St Vincent’s hospital.

Some

of

the 1978-ers marching in the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras in

2008.

Photograph: Jane Dempster/AAP

Helping

bail the men was Barbara Ramjan. It was nearly a year since

the

dramatic night of her election as the president of the

Sydney

University Students’ Representative Council, the night the

man she

beat, Tony Abbott, punched the wall beside her head.

Now

she was dealing with bewildered students, obstructive police

and

tearful gay solicitors. The last of the men bailed about

8.30am on

Sunday morning complained of a busted eardrum after being

bashed in

the police garage.

For

no particular reason except to prolong their ordeal, the

women

prisoners had been removed to central police station. There

they were

very, very slowly fingerprinted. The last of them was not

released

until 9.30am.

That

night on television, the then NSW premier Neville Wran

claimed the

demonstrators had had “a pretty good go … and I don’t

suppose

that it’s unexpected that the police have taken exception to

a busy

thoroughfare in Kings Cross being completely blocked off at

midnight.”

All

those charges were eventually dropped. Police commanders

were shown

to have lied in court

That

was a signal to police. Next morning in a cold drizzle up to

150

officers blockaded the steps of the Liverpool Street courts.

There

followed a battle that lasted most of the day between police

and the

magistrates to allow access to the courts. Despite order

after order

from the magistrates, the police declared: “The courts are

closed.”

The

crowd grew restive. Eggs were thrown. Three women who tried

to climb

over a high balustrade were tossed back into the crowd.

There were

more arrests. A police photographer shot rolls of film.

Solicitors

were threatened.

A

magistrate ordered Ramjan to be allowed into the building to

bail the

new prisoners. I watched police push her down the stairs

instead. She

somehow kept her footing. After all these years she puts

that down to

“Girl Guide training”. She made it into the building at

last.

Soon

after lunch, the police gave way. They’d made their point.

The

public entered to watch the magistrates grind through

formalities:

one charge of malicious injury to a police uniform, three

charges of

assault, four of offensive behaviour, five of failure to

observe a

direction, nine of resisting arrest, 10 of unseemly words,

18 of

hindering police and 19 of unlawful procession.

All

those charges were eventually dropped. Police commanders

were shown

to have lied in court. Protests continued all through that

winter. It

was at this time that a cohort of young solicitors came out.

The law

was at last seen for what it has always been: one of the

great gay

professions.

Mardi

Gras became a great Sydney event, at first commemorating

that 1978

shemozzle. But in an absolutely Sydney development, it

shifted from

winter to summer to celebrate itself – and to keep calling

for law

reform. It was 1984 before Wran stared down the churches and

the

Catholic flank of the Labor party to decriminalise gay sex

in NSW.

Marriage equality: why knot?

Read

more

The

police changed. This year the NSW police gay and lesbian

liaison

officers will march in Mardi Gras as they have done for the

past 20

or so years. Bill Shorten will be among the squad of

politicians

turning out for the celebrations.

And

as a curtain-raiser this week the NSW parliament will debate

an

apology for 1978 and what Liberal MP Bruce Notley-Smith

calls “the

struggles and harm caused to the many who took part in the

demonstration and march both on that night and in the weeks,

months

and years to follow”.

Ken

Davis, one of the organisers of the first march is weighing

up

whether to attend the ceremony. He welcomes the apology

after all

these years but wonders where we are on the bigger question

of

freedom in a city of lockout laws and harsh bans on

processions.

“We

got law reform,” says Davis, “but police control of

public life

is much more extensive now than it was in 1978.”

Friday

essay: on the Sydney Mardi Gras march of 1978

The

Conversation February 19, 2016 6.18am AEDT

The

1978 Mardi Gras started as a peaceful march and degenerated

into a

violent clash with police. The

Pride History Group

Author

English

for Academic Purposes Specialist, Anthropologist, Centre for

English

Teaching, University of Sydney

Disclosure

statement

Mark

Gillespie is affiliated with The '78ers.

On

April 27, 2015, Christine Foster, a Liberal Party councillor

and the

sister of the then Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott,

moved a

motion at the Sydney City Council calling for a formal

apology to

the original gay and lesbian Mardi Gras marchers.

It

was passed unanimously. The NSW Parliament is expected to

debate

a motion

to offer such an apology in

the first sitting of Parliament in 2016.

Is

a formal apology warranted?

To

answer this question, some understanding of the prevailing

oppressive

social conditions affecting the lives of sexual minorities

(now

termed GLBTIQ communities) in Australia in the 1960s and 70s

is

required.

What

is needed, too, is a better knowledge of the actual,

momentous events

that took place in Sydney between June and August 1978, when

violent

social unrest and public protests on the streets erupted

with

far-reaching effects for Australia that can now be seen in

historical

context.

The

march of 78

On

a cold Saturday night in Sydney on June 24, 1978, a number

of gay

men, lesbians and transgender people marched into the pages

of

Australian social history. I was one of them.

Several

protests and demonstrations were organised during June that

year to

commemorate the 1969

Stonewall riot in

New York and to demand civil rights for Australian lesbians

and gay

men.

Gay

activists in San Francisco had asked the Gay Solidarity

Group in

Sydney for support in their campaigns in California and the

word had

got out. At Taylor Square, where we assembled, I was

impressed by the

turnout (a report in The Australian estimated the crowd at

about

1,000 people at this early stage of the night).

The

early rainbow nature of the movement was evident, with

transgender

and Aboriginal people and people from migrant backgrounds

all mixing

in. We were a diverse and spirited group of a few hundred

mostly

younger men and women ready to march down Oxford Street to

Hyde Park,

along a strip that was becoming the centre of gay life in

the city.

The

atmosphere was more one of celebration than protest. Little

did we

know then that, by the end of the night, many of us would be

traumatised and our lives changed forever.

As

a young émigré in my twenties, from the Queensland bush,

like many

gay men and lesbians from the country in those days, I was,

in

effect, an internally displaced person. We were refugees in

our own

country.

Having

arrived in Sydney seeking refuge from the never-ending

police state of mind that

was life under the Joh Bjelke-Petersen Queensland

government, I was

renting a studio flat in Crown Street, Darlinghurst, at the

time.

All

through history, cities have offered people like me a

measure of

escape from oppression and persecution. But in 1978, even in

a big

city like Sydney, refuge and security could not always be

found and,

without even basic human rights, we were always vulnerable.

As

a high school teacher working for the NSW Department of

Education,

“coming out” posed a major risk for me – it could mean the

loss

of my job. For the those who were subjected

to electric shock treatment in

the 1970s at the old Prince

Henry Hospital in

Little Bay, it could even mean losing your mind.

Living

a “double life” was a means of survival. Gay people’s lives

were wrapped in stigma and shame.

The

real unspoken tragedy of the times was the loss of the lives

of so

many wonderful young people who struggled with their sexual

identities and, unable to deal with all the pain and shame

inflicted

on them, ended up committing suicide.

The

Stonewall Riot, which had occurred nine years earlier, far

away in

Greenwich Village on Manhattan in New York, marks the modern

era of

“homosexual liberation”. This oft-quoted term was

popularised as

early as 1971 by Dennis

Altman,

the Australian academic who became a leading voice of the

movement.

Altman continues

today to

chronicle and interpret the movement. The violence, unrest

and

resistance of the Sydney Mardi Gras of 1978 has clear

parallels to Stonewall.

Back

to the march

We

started off from Taylor Square in a festive mood. Chants

rippled

along the marchers, strangers joined hands and we sought to

bring

people out of the bars and into the streets to join us. Some

did come

out of the bars and joined us; others lined up and watched

the parade

but did not join in.

I

heard the commonly used Australian put-down of those times,

“poofters”, hurled at us. “Ratbag poofters”, too. When we

reached Hyde Park we were denied entry.

Confusion

reigned and an officer in authority appeared intent on

breaking up

the march. His derogatory tone of voice and the way he

hurled insults

and abuse angered all

within earshot.

It

soon became clear that our open-back truck that would have

provided

the disco music for a party and a platform for speeches in

the park

was to be forcefully confiscated and the driver arrested. We

then

realised it would be a mistake for us to enter Hyde Park at

all.

At

the front of the march I remember a few split seconds of

initial

doubt that we would be able to do it, and then, in perfect,

bold,

spontaneous unison, at our success in breaking through the

cordon of

police across College Street, we shouted, “On to the Cross!”

(Kings Cross).

With

an exhilarating surge of energy we turned from College

Street into

William Street. Propelled onwards with hundreds joining in

behind us,

we turned left into Darlinghurst Road into the heart of

Kings Cross.

We were sick and tired of being criminalised, pathologised,

demonised, of being made to hide who we were and having our

rights to

live as human beings denied.

That

night we were in the streets and we were determined to get

our

message to as many people as possible. After marching down

Oxford

Street and seeing our numbers swell as many people came out

of the

coffee shops, bars and hotels to join us, now we wanted to

call on

everybody in the Cross to listen to our chants and come out

and

support us as well. We chanted: “Out of the bars and into

the

streets!”

We

wanted the whole world to hear our cries for freedom from

the

oppression that characterised our lives. In numbers,

suddenly,

wonderfully, we were unafraid. Here there was a direct

parallel with

Stonewall, for as

with the NYPD,

the NSW police force faced an unexpected and vigorous

resistance.

As

determined as they were to put us back in our closets there

was no

stopping us. Now we were coming out. And now we had straight

people

willing to join in and support us. In Darlinghurst Road in

Kings

Cross we were cut off and ambushed with hundreds of police

with

dozens of wagons blocking us in front and from behind.

These

were critical moments, because in truth the crowd would most

likely

have dispersed at this point.

Yet

the real violence was about to begin. It was there in

Darlinghurst

Road that we faced the most brutal onslaught of the whole

night. The

police, arriving in numbers, took advantage of the semi

darkness of

the night, unleashing a reckless and ugly attack on the

marchers.

They

acted as if they had a licence to inflict as much injury as

they

could and I feared there would be dead bodies everywhere if

they had

guns in those paddy wagons and were to open fire. Despite

that fear

we did not run, we fought back, resisting arrest as the

police

wielded their heavy batons indiscriminately.

The

Pride History Group, Author provided

The

more we were assaulted the more we resisted. The

group-solidarity had

taken hold as we tried to stand our ground, rescuing

“brothers”

and “sisters” from the clutches of the police as they were

being

forced into paddy-wagons. I distinctly remember the way that

the

police near the El Alamein Fountain targeted women for

arrest, in

particular, and the smaller and more vulnerable among us.

The

first Mardi Gras is often described

as a riot but

I didn’t see it that way. It was a very defiant act of

resistance

that proved a turning point. We were willing to stand up, to

resist.

We were people too; our sexualities may have been diverse

and

different but that did not make us any less human than

others.

The

discriminatory attitude of the police and the violence they

meted out

to us seemed to represent in highly symbolic and condensed

form the

very pain, humiliation and suffering that society as a whole

constantly inflicted on us as lesbians and gay men.

Some

53 men and women were arrested, all of whom – unhelpfully –

had

their names

and occupations subsequently published in

The Sydney Morning Herald. Many lost their jobs or housing

as a

result.

Gail

Hewison, one of the women detained, described to me the

whole

experience of being locked-up without charge as one of shock

and

trauma. She had all her possessions taken away from her

including her

glasses. She told me she could hear the sounds of a man

being

horribly beaten in another cell. Then, after a while she

also began

to hear the supportive chants of the crowds gathering

outside.

In

front of the police station, close to Oxford Street and

Taylor Square

where the march had started hours earlier, battered and

bruised,

hundreds of us gathered in an enraged state shouting, “Let

them

free!”. We continued the refrains from our earlier chants:

Two

four six eight, gay is just as good as straight!

Looking

out at the angry crowd the police inside the station must

have been

apprehensive about what would happen next. They were greatly

outnumbered and for some moments as we inched closer and

closer, you

could sense an urge on the part of the crowd to takeover the

police

station, to demand the jailers keys and so to release our

brothers

and sisters.

Over

the years I have often wondered why we didn’t storm the

building

then and there. Strangely after a short period of silence

somebody

started to sing the Afro-American spiritual “We shall

overcome”

and the whole crowd joined in:

We

shall not, we shall not be moved

We shall not, we shall not be moved

Just like a tree that’s standing by the water

We shall not be moved

We shall not, we shall not be moved

Just like a tree that’s standing by the water

We shall not be moved

Reflecting

on this now I would like to think that, despite the

provocation on

that night itself and the centuries of violence that had

been

perpetrated upon us, we as a collective knew instinctively

that

violence was one of our main grievances and we had a mission

to

resist it and fight against violence using other means.

Someone

in the crowd cried out, “I am a lawyer. Are there any other

lawyers

or solicitors here? We need to raise bail money!”. The

campaign to

win the legal battles was now well underway, culminating in

1984

when homosexuality

was decriminalised in the NSW Parliament.

This

brief narrative of the first Mardi Gras is told because the

events of

that night, their causes and repercussions can now be placed

in

clearer historical perspective and they help us to

understand why

keeping politics at the centre of the annual Mardi Gras is

so

important.

Facing

the HIV epidemic

As

Dennis Altman pointed out in The

End of the Homosexual? (2013),

it was the precise timing of the Mardi Gras leading to the

decriminalisation of homosexuality in NSW in 1984 that

ultimately

helped save thousands of Australian lives in the HIV

epidemic that

hit Sydney hard in 1985.

The