Retail giant Aldi faces claims of wage theft and breaking the law

With no finish time on his roster, Mr Joyner - a permanent part-time worker, not a casual - does not know what time he will leave work at Aldi's Stapylton distribution centre.

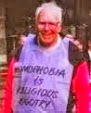

Paul Joyner said Aldi's work arrangements causes disruption to family life: "The school pick-up time would be the hardest thing." Photo: Bradley Kanaris

The father-of-three also said he had worked for free for the

retail giant to pay off "negative hours" accumulated because he was not

given enough shifts to complete the hours he is contracted to work.

"I was at minus-78, and now I work extra to pay back those hours," Mr Joyner said. "And I don't get paid."

His claim is "categorically rejected" by Aldi, which said in a statement: "The enterprise agreement provides for an averaging arrangement of hours and employees receive payment for every hour worked."

Mr Joyner, who used to coach his son's soccer team, said the uncertainty caused disruption to his family life. He said it also made it difficult to make commitments such as taking his children to sporting events and leisure activities.

"The school pick-up time would be the hardest thing," Mr Joyner said.

"We get it drummed into us 'You don't have a finish time'."

This lack of certainty created other worries for workers with children, he said. "Childcare's until 6 o'clock and then you start paying $2 every minute. So 10 minutes – there's 20 bucks. You do that a couple of times a week and it soon adds up."

"I was at minus-78, and now I work extra to pay back those hours," Mr Joyner said. "And I don't get paid."

His claim is "categorically rejected" by Aldi, which said in a statement: "The enterprise agreement provides for an averaging arrangement of hours and employees receive payment for every hour worked."

Mr Joyner, who used to coach his son's soccer team, said the uncertainty caused disruption to his family life. He said it also made it difficult to make commitments such as taking his children to sporting events and leisure activities.

This lack of certainty created other worries for workers with children, he said. "Childcare's until 6 o'clock and then you start paying $2 every minute. So 10 minutes – there's 20 bucks. You do that a couple of times a week and it soon adds up."

Aldi is celebrating its one year anniversary this year.

Tim Gunstone, an organiser for the National Union of

Workers, said Aldi's "peculiar employment arrangements" were stressful

for workers.

"Workers are sent home early when it suits Aldi, but when the work is busier, or poorly planned by management, workers are told they have to stay at work until everything is finished," Mr Gunstone said.

"The lack of any finish time on rosters makes it impossible for workers to refuse the overtime they are being required to do."

Mr Gunstone said the NUW believed Aldi's employment practices were against the law because permanent part-time workers should be provided with the hours described in their employment contract in each pay period.

Mr Gunstone added: "When a worker is required to work without pay to work off "negative hours" this is in effect wage theft."

However, an Aldi spokeswoman said: "The suggestion that employees work unpaid overtime is categorically rejected."

She said workers received payment for their "contract hours" even if they do not work the required amount of time.

"They are then rostered to work additional hours above their contract in subsequent fortnights, to complete the hours for which they have already been paid," she said. "The Fair Work Commission has examined and approved this work arrangement as being lawful and suitable."

But the NUW is vowing to renew the fight and lodge a dispute with the Fair Work Commission if Mr Joyner's concerns cannot be resolved with Aldi.

"We would expect that such a dispute would be resolved by arbitration, and expect that a Commissioner would find that Paul was owed money for every hour he worked without payment while 'paying off negative hours'," Mr Gunstone said. "This could create a substantial underpayment affecting thousands of Aldi workers."

Associate Professor Angela Knox, from the University of Sydney Business School, questioned whether the arrangement was "good practice"

.

"There is a difference between a practice being legal and it being good, especially for workers," she said.

"This type of practice has been used in large chain hotels for over a decade but there are more 'checks and balances' in place, normally."

But Associate Professor Knox said caps were usually imposed to prevent workers accruing a debt as large as 78 hours.

She questioned whether Aldi's workers understood the ramifications of the provision, which created large "negative hours" balances.

"The specific details that would explain how the system operates are not outlined, hence managerial prerogative is maximised," she said.

Aldi's spokeswoman said salaries were above market rates, while staff turnover was low: "Our working conditions are also considered to be some of the best in the industry, with independent employee satisfaction surveys returning consistently high scores."

Mr Gunstone said he had spoken to more than 100 Aldi workers who had concerns about the company's practices but "they felt they had no choice but to accept it".

He said Aldi also tried to prevent its workers engaging with the union - a claim contested by the company.

"Aldi routinely place managers in lunchrooms when union organisers visit sites – for the explicit purpose of monitoring the unions engagements with workers," he said. "At Paul's workplace managers have repeatedly interrupted organiser conversations with employees."

Mr Joyner, who is a union delegate, said many of his colleagues shared his concerns about Aldi's work practices but feared the consequences of speaking out.

"They'd like to say stuff too but they're scared," he said.

With the impending arrival of retailers such as Amazon, Mr Gunstone said the conditions for warehouse workers were at risk.

"Aldi's work practices are one example of the ways in which these jobs are increasingly becoming insecure, and how many major retailers are increasingly involved in a race to the bottom when it comes to job security and casualisation," he said.

"Amazon – which is setting up in Australia – are known for their low wages and anti-union attitude."

Larissa Andelman, a barrister who practices in industrial law, said the Australian labour market had a very high level of casualisation, and the line between casual and permanent employment was often blurred.

"However the rise of 'zero hour' contracts in England has caused a significant financial hardship to those affected and there has been political and legal action to limit and cease these kind of arrangements," she said.

"It would be most unfortunate if these kind of arrangements were found lawful in Australia as they impact adversely on the most low paid and marginalised workers who are often young people and women."

"Workers are sent home early when it suits Aldi, but when the work is busier, or poorly planned by management, workers are told they have to stay at work until everything is finished," Mr Gunstone said.

"The lack of any finish time on rosters makes it impossible for workers to refuse the overtime they are being required to do."

Mr Gunstone said the NUW believed Aldi's employment practices were against the law because permanent part-time workers should be provided with the hours described in their employment contract in each pay period.

When a worker is required to work without pay to work off "negative hours" this is in effect wage theft."The second is that Aldi are requiring employees to work without payment when they are "paying off" the negative hours," he said. "The third is that permanent workers must be provided with a start and a finish time for their rostered shifts."

Tim Gunstone, an organiser for the National Union of Workers.

Mr Gunstone added: "When a worker is required to work without pay to work off "negative hours" this is in effect wage theft."

However, an Aldi spokeswoman said: "The suggestion that employees work unpaid overtime is categorically rejected."

She said workers received payment for their "contract hours" even if they do not work the required amount of time.

"They are then rostered to work additional hours above their contract in subsequent fortnights, to complete the hours for which they have already been paid," she said. "The Fair Work Commission has examined and approved this work arrangement as being lawful and suitable."

But the NUW is vowing to renew the fight and lodge a dispute with the Fair Work Commission if Mr Joyner's concerns cannot be resolved with Aldi.

"We would expect that such a dispute would be resolved by arbitration, and expect that a Commissioner would find that Paul was owed money for every hour he worked without payment while 'paying off negative hours'," Mr Gunstone said. "This could create a substantial underpayment affecting thousands of Aldi workers."

Associate Professor Angela Knox, from the University of Sydney Business School, questioned whether the arrangement was "good practice"

.

"There is a difference between a practice being legal and it being good, especially for workers," she said.

"This type of practice has been used in large chain hotels for over a decade but there are more 'checks and balances' in place, normally."

But Associate Professor Knox said caps were usually imposed to prevent workers accruing a debt as large as 78 hours.

She questioned whether Aldi's workers understood the ramifications of the provision, which created large "negative hours" balances.

"The specific details that would explain how the system operates are not outlined, hence managerial prerogative is maximised," she said.

Aldi's spokeswoman said salaries were above market rates, while staff turnover was low: "Our working conditions are also considered to be some of the best in the industry, with independent employee satisfaction surveys returning consistently high scores."

Mr Gunstone said he had spoken to more than 100 Aldi workers who had concerns about the company's practices but "they felt they had no choice but to accept it".

He said Aldi also tried to prevent its workers engaging with the union - a claim contested by the company.

"Aldi routinely place managers in lunchrooms when union organisers visit sites – for the explicit purpose of monitoring the unions engagements with workers," he said. "At Paul's workplace managers have repeatedly interrupted organiser conversations with employees."

Mr Joyner, who is a union delegate, said many of his colleagues shared his concerns about Aldi's work practices but feared the consequences of speaking out.

"They'd like to say stuff too but they're scared," he said.

With the impending arrival of retailers such as Amazon, Mr Gunstone said the conditions for warehouse workers were at risk.

"Aldi's work practices are one example of the ways in which these jobs are increasingly becoming insecure, and how many major retailers are increasingly involved in a race to the bottom when it comes to job security and casualisation," he said.

"Amazon – which is setting up in Australia – are known for their low wages and anti-union attitude."

Larissa Andelman, a barrister who practices in industrial law, said the Australian labour market had a very high level of casualisation, and the line between casual and permanent employment was often blurred.

"However the rise of 'zero hour' contracts in England has caused a significant financial hardship to those affected and there has been political and legal action to limit and cease these kind of arrangements," she said.

"It would be most unfortunate if these kind of arrangements were found lawful in Australia as they impact adversely on the most low paid and marginalised workers who are often young people and women."

No comments:

Post a Comment